Prompt 309. Beethoven & the Blues

Jon Batiste on spontaneous composition & Hollynn Huitt on imagination

I’m Trying Something New—

As I navigate a new health challenge, a handful of friends are occasionally filling in as guest hosts of the newsletter. Today, in my stead, you’ll hear from the Oscar, Emmy, Golden Globe, and five-time Grammy award-winning musician Jon Batiste—also known as my husband. I’m grateful to him for stepping in and so honored to share his brilliant words and wondrous mind with you today.

—Suleika

Hello! Hello! Hello!

My name is Jon Batiste, and I’m excited to be filling in today for my beautiful wife, Suleika, and to have a chance to speak to this incredible community about authenticity, imagination, and Beethoven and the blues.

I want to start with a little story about something that happened a year ago, when I was interviewed by the journalist Chris Wallace for his show Who’s Talking? He was asking me about World Music Radio, my album where I wanted to reimagine what they call “world music,” which is often looked at through a condescending Western lens, and at the same time expand the narrow notion of popular music, and he wondered if I could show him what it looks like to break a musical barrier. “Of course,” I said. And since we were sitting in a music hall at my alma mater, Juilliard, I started in with Beethoven’s “Für Elise”—first playing it in the recognizably classical style, then a few bars in, shifting into a blues vibe, then to gospel, then back to a classical riff at the end.

I hadn’t prepared or practiced it—extemporizing in that way is natural to me. I’ve always had different instincts, and because I’ve been exposed to genres like jazz, blues, and gospel, when I started taking piano lessons and studying the classical repertoire, I found myself wanting to change notes or add flourishes—not to buck tradition necessarily, but as a way of being in conversation with the composer. Though it goes the other way too; sometimes I want to play a jazz piece more predictably.

After the interview, I didn’t think much about that Für Elise interlude. It was a minute-long clip in an hour-long interview, and like I said, it’s so natural to me. But the network posted it online, and people were into it, and it was sparking all these questions. People were like, “How’d you do that?” Or even, “Can you do that?’”

Beethoven is one of those artists that some people will say, “No, you can’t”—that you can interpret what’s written on the page, but you can’t add notes or revise sections. If you do, they’ll clutch their pearls and say, “That’s sacrilege.” But from what we know, Beethoven himself was a master improviser—or as I like to call it, spontaneous composition. Improvisation is often looked at as less significant and less thoroughly rigorous than composition. The implication is that it’s unstudied, unrehearsed, out of nowhere—when, really, some of the greatest compositions in history may have been made upon the spot, having come out of decades of practice and study.

Beethoven’s music is in some ways the simplest, as memorable as a nursery rhyme. But it’s also the most complex and innovative, like when he uses duple- and triple-meter at the same time. We’ve never heard Beethoven play, but if he’d been alive in the Jazz Age, I believe he would have had the same spirit as Duke Ellington, who was one of the most sophisticated composers of any era, who deployed some of the most sophisticated forms, and whose greatest compositions were often inspired by things that happened in the moment on stage.

So that’s one point in favor of artistic license, but in my mind, the more important point is that when we allow forms to evolve, we find new frequencies. Throughout history, when people decided to go against the standard practice, to depart from the norm—whether in music or some other medium—it has led to an expansion or refinement or general improvement of the human condition. How many times has that happened? That’s pretty much the whole history of any positive evolution in creativity and culture: somebody takes what has come before, and while respecting it, while revering it, they bring it into the present to create the future.

Which is why I think a lot of people kept asking a third question about that Für Elise clip: “Why hasn’t this happened more?” And that question really inspired me. For a while, I’d been talking with my piano teacher about recording a series of albums in this style. We’d talked about how far I’d come since I started taking lessons from him at nineteen, and how I’d gotten to a certain level in my piano playing, and how, after spending time learning all these different traditions, I’m able to meet this music at this moment in history. I’m able to bring the influence of all the music that exists now that didn’t exist when Beethoven was around, and to do it authentically. Beethoven is who he is, and I happen to be a channel in this time, and I can extend it and add to it in my way.

And even though this rendition emerged from my experience—from my specific background and perspective and interests—it touched something universal. People felt what I felt. They too felt a void, and that’s what made the change so welcome when it arrived. So I said to myself, Maybe it’s time to record this. This is how most of my creative direction comes, but this felt very pure because it’s just the piano. So I went to our house in Brooklyn and down to the studio, and in two days, I recorded a new album called Beethoven Blues, which will be out in about two weeks—though the first single, Für Elise, is available to listen to and watch now.

I was once talking to my good friend, the legendary hip hop producer No I.D., and he said that it’s very rare to have music that can fit in all of the areas of life. Some music is just for when you want to rage or cry. Some music is only for dancing. It’s rare to have a piece of music you can play at a wedding, a funeral, and when someone is born, when you’re on the way to your day’s work or your life’s work, in the city, or on the farm, rare to have music you can play at large gatherings, and that you can also listen to alone, when you’re going to sleep, or during some ritual like prayer, or just on in the background as you’re going around your house. I hope this album is like that.

The legendary Thelonious Monk once said, “A genius is the one who is most like himself.” I love that quote because it speaks to authenticity. It speaks to the need to be exactly who you are, and to do the thing that is most innate to you. Nobody else has your specific talents, your interests, your experience, your skills, or your perspective. If you channel that kind of authentic expression, you bring things into the world that nobody else ever has or will. All you need is some imagination—because it’s up to you to create the blueprint for the thing you want to see in the world.

I love imagination. I love that something in your mind that’s not real can become real. You can bend and shape and mold and push back against the world around you. If no one has done it yet, you can think about doing something. It doesn’t have to be make-believe; it can be real.

So now I’m gonna pass the baton to the writer and Isolation Journals community manager, Holly Huitt, who has a special essay and prompt for you called “Eyes in the Night,” where she writes about the things we see and what they could be, and how seeing things in a different way can transform you.

Thank you, and God bless you, and I love you even if I don’t know you—

Jon

An Item of Note—

In last week’s meeting of the Hatch,

shared a poem by the brilliant Ada Limón and the most generative writing exercise. As one community member wrote, “What a wonderful experience and so worth the time. So many thoughts, ideas, emotions and so much to put into writing.” If you missed it, you can find the reading, prompt, and community discussion at our Notes from the Hatch: The Huge Beating Genius Machine.

Prompt 309. Eyes in the Night by Hollynn Huitt

The first time I wore the headlamp I was frightened by its power. I could see clear across the valley. I imagined the nosy man who lived opposite to me—his driveway light a mere spark in the distance—standing up from his suede armchair and peering out the window with alarm. I liked that idea.

What I didn’t like was that I could see virtually nothing outside of the beam. My peripheral vision was deadened to pure black, the bodies of my animals reduced to pairs of gleaming eyes. I had been doing chores without illumination but now, with changing light, the walk down “Apple Alley”—the steep hill slick with rotten fruit from the trees above—had become too risky. There are too many creatures, human and otherwise, who depend on me for me to sprain an ankle or fracture a wrist, so at my husband’s urging, I had begun making my way to the barn wearing his brand-new, high-powered headlamp.

As I walked, I scanned my surroundings, sweeping my cycloptic eye everywhere, from fenceline to treetop. There were my two dogs, identifiable by their differently shining eyes. There was one cat staring at me from a hollow in an apple tree, and his brother peering at me from behind a pile of trash bags filled with shorn wool. But then there were more eyes—eyes I couldn’t account for. Was that a raccoon, or perhaps a possum? What would I do, I asked myself, when I saw a set of eyes, or many sets of eyes, that I didn’t want to see?

But what if these weren’t the eyes of coyotes or hungry black bears or an unwelcome human, but something else entirely? And just like that, I unlocked the most marvelous guessing game. Does that shining pair of eyes by the compost heap belong to a goofy, lop-armed monster with luxurious purple fur? Are the tiny glinting eyes by the gate those of a nearsighted milkweed plant who, not expecting the likes of me, didn’t turn away in time?

I imagine how I must appear to these fantastical creatures. I’m a single bright eye. I’m capable of freezing them in my beam. I am a superhero, or a celestial being, or a UFO who comes in peace despite my confronting and somewhat alarming methods. I make excuses to stay out longer and longer, walking the land, letting my beam sweep, letting my imagination roar.

Your prompt for the week:

Think back to a game of make-believe you once played or still play today. Describe it in great detail, especially how it made you feel, and what it gave you—whether a sense of power, an escape, or a sojourn in wonder.

If you’d like, you can post your response to today’s prompt in the comments section, in our Facebook group, or on Instagram by tagging @theisolationjournals. As a reminder, we love seeing your work inspired by the Isolation Journals, but to preserve this as a community space, we request no promotion of outside projects.

Today’s Contributor—

Hollynn Huitt is a writer and the community manager for the Isolation Journals. She holds a BFA in writing from the Savannah College of Art and Design and an MFA in fiction from the Bennington Writing Seminars. She has stories published in Stone Canoe, Hobart, PANK, and X-R-A-Y. She lives in an old farmhouse in central New York with her family and many animals, which she writes about on her Substack, far away.

For some more wondrous extemporizing by Jon, see—

& for more paid subscriber benefits, see—

A Creative Heart-to-Heart, a raw, unfiltered conversation with Suleika and Jon where they talked about getting started, the power of no routines, and how they use creativity to marry their joys and sorrows

Behind the Scenes of American Symphony, a video replay of a conversation with Suleika and Jon and Matt Heineman, the director of their documentary, where they talked about “peak compartmentalization,” learning to say “I’m not okay,” and how Matt squirreled his way into filming at the Grammys

On Failure, a video replay of Suleika’s Studio Visit with Jon, where they talked about “getting your rejection in,” how you’re not growing if you’re not failing, and where Jon shares the recipe for his ma’s red beans

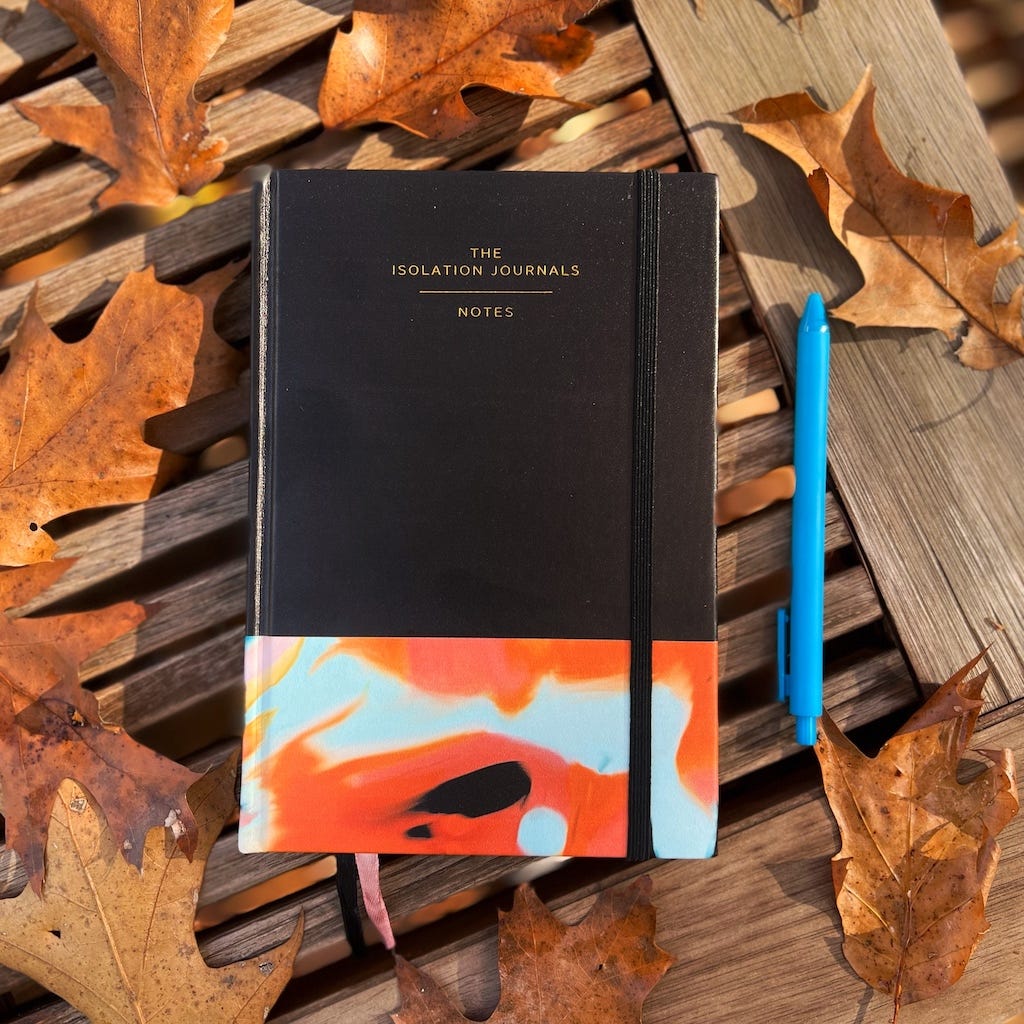

Our Isolation Journal No. 1—

If you’re looking for a fresh start for fall, treat yourself to our custom journal! It has all of our favorite features: the perfect size to tote around wherever you go, ink-bleed proof paper, and numbered pages for easy indexing—and for extra inspiration, we printed our Isolation Journals manifesto on the flyleaf. To get yours, click the button below!

Greetings from Hong kong dear Susu on my solo grand tour of Asia to celebrate my big 80. So happy to come back to my hotel room after a day of wanderlust to find the familiar and the extraordinary. thank you for sharing your beautiful Jon. Truly, you are both gifts from the gods Muchas Gracias. With gratitude.💖

I am a newly diagnosed with rare blood cancer, and the diagnosis is sending me deep into myself to learn who I am in this new context of sickness. I am re-thinking my clothing, the way my home is arranged and eve decorated. I pulled out an old favorite, which is a beautiful drawing of Beethoven, celebrating art in radio. My own musical background includes classical and jazz, too. In the 80's as a college student, I simply could not play jazz on my violin - everything came out sounded wrong. So I learned a new instrument - the bass. I could do it on the bass. Now all these many years later, the violin is gonna come back out for more exploration. Thank you from the bottom of my heart for you.