Hi friend,

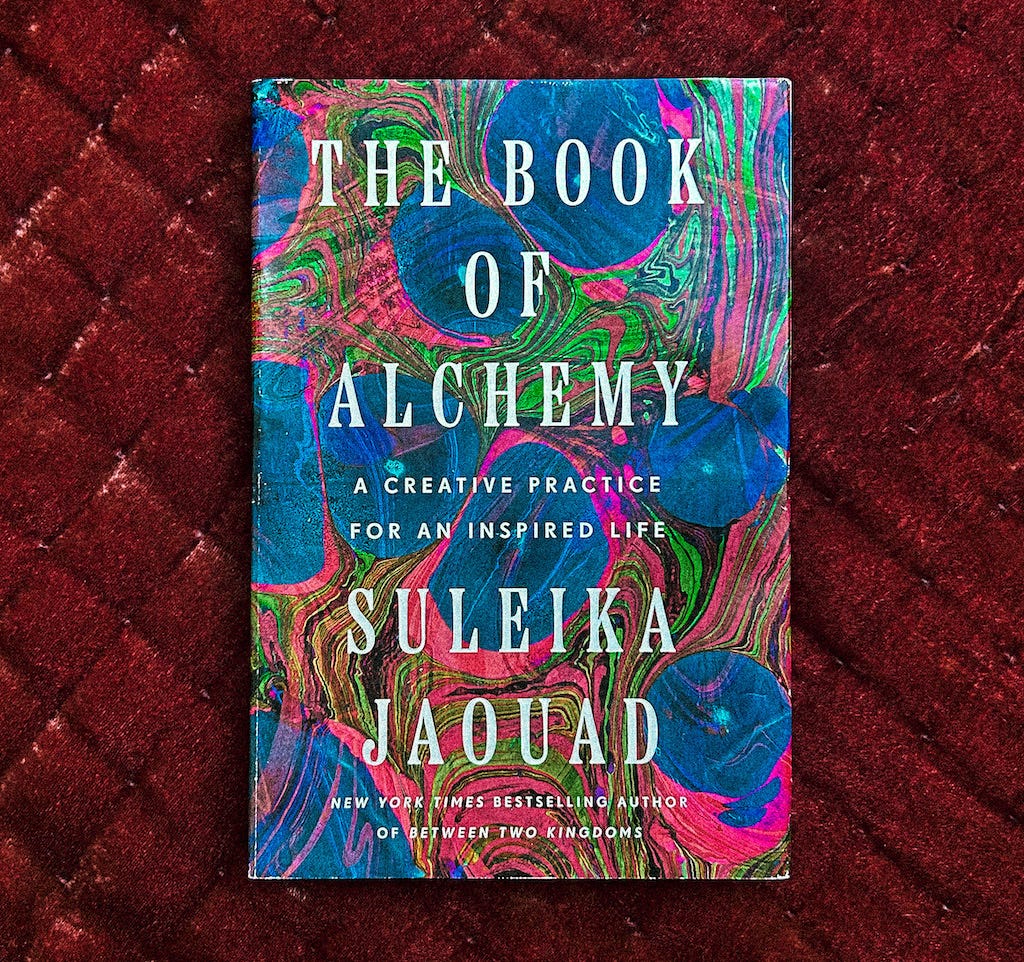

Back in the fall, after I handed in the final manuscript of The Book of Alchemy, I started dreaming about the book tour. But rather than the typical format—reading from my book and taking a few audience questions—I was excited by the idea of creating something unconventional, something that enacted the essence of the book. I wanted to bring creative alchemy to life onstage.

As exciting as that felt, it was also anxiety-inducing, given that I had just learned my cancer was back and had restarted chemo. For people with chronic illness, any discussion of the future raises the question, Will I be well enough? (Beneath that, for some of us, is the somewhat dramatic but nonetheless real question, Will I still be here then?) But this book is the culmination of so much—of grappling with illness and aftermath, of what I’ve learned from a lifetime of cultivating a creative practice and the lifeline of a creative community, just to mention a few—and I wanted to honor and celebrate that.

So I asked some trusted friends, including my husband Jon and our dogs, to sit down with me and help me imagine what this book tour could be. And after some initial meanderings, where I posed all kinds of questions and tried to tease out a theme, Jon said, rather decisively, “There’s one really simple question for this tour: Who do you want to hang out with?”

To be clear, he didn’t mean “Who’s going to be in the green room beforehand?” or “Who will you get a drink with afterwards?” What he meant was, “Who do you want in that room?”

And my answer was: “You.”

The truth is, I’m not well enough to pull off a multi-city tour on my own; I can’t do it without a caregiver. But more than that, I wanted Jon there because we’re each other’s most trusted collaborator. The Book of Alchemy is dedicated to Jon, my partner in life in creativity, who always inspires me to dream big. For many of us, it’s tempting to play it safe, to focus on all the reasons why something won’t work, to curtail our dreams before they’ve even formed. But Jon has taught me by example that nothing is off-limits. He doesn’t play by the rules, he doesn’t abide by genres, he doesn’t confine himself. Every few months, he comes home with a brand new instrument, a saxophone, a guitar, a clarinet, and he wanders around the house with it, trying it out. It’s not like he masters it instantaneously (I now know that a beginner on the clarinet can sound a lot like a dying goat), but for him, curiosity, wonder, and growth are the metric of success, rather than the outcome. He knows there’s value in learning new things, in pushing yourself beyond yourself. That mindset allows him to wriggle free of the fear of failure, to completely reframe it: There is no failure, it’s all learning.

Jon inspires me to give myself permission, to try new things and to do so in a big way—not by paying some unimaginable cost, not by risking complete physical depletion or financial ruin, but by being creatively daring. And so that’s what I’ve done: I’m excited to say that my unconventional book tour is coming. Jon is going to join me, along with other special guests. We’ll tell stories. We’ll make music. We’ll ponder the big questions. We’ll laugh, dance, and likely share some tears. We’ll be inspired to tap into possibility and expansiveness and wonder.

I’ve never done anything like this before—which honestly makes me nervous—but I know it’s going to be so special. And since this book would not exist without the Isolation Journals community, we’ll be offering tickets to you first, starting with a special pre-sale on Tuesday for paid subscribers. Keep an eye out for an email with all the details!

In the meantime, I have an essay and prompt for you on what it means to be ambitious, to dream without limits. It’s called “What You’re Made Of,” by the brilliant novelist Ann Napolitano, whom I adore. (I devoured her book Hello Beautiful, and you may have too. It had the distinct honor of being Oprah’s 100th book club pick.) This piece is so gorgeous and powerful, and it’s already inspiring me to dream even bigger. For a lesson in letting go of “good enough” and harnessing your inner growl, read on.

Sending love,

Suleika

Some Items of Note—

If you missed last week’s meeting of the Hatch, our monthly creative gathering for paid subscribers, we’ve posted a video replay! In it,

spoke about the concept of karma and invited participants to pen their own personal “repair kits.” It was a truly beautiful and nourishing hour—you can access it here!As for the next gathering of the Hatch, it’s scheduled for March 16, 2025, from 1-2pm ET.

will reflect on how we can turn isolation into creative solitude and connection. Mark your calendar!

Prompt 327. What You’re Made Of by Ann Napolitano

My father signed me up for our local soccer league when I was five years old, and volunteered himself to be the assistant coach. This was a leap for both of us: I was a shy child who carried a book everywhere, and my dad had been forbidden to play sports his whole life because of high blood pressure. Before the first practice, my mother read aloud the entry about soccer from our encyclopedia set, so he could get a sense of the basic rules. I suspect the reason my dad took this leap was because my parents were concerned about how shy, bookish, and quiet I was. The highlight of my week was my visit to the town library, where I filled a duffel bag with novels that I giddily disappeared into until the next library visit. My parents thought I would benefit from playing with other children, as well as some physical activity, and a soccer team provided both.

Luckily, my dad hit it off with the head coach—a twinkly-eyed fireman—and they ended up coaching together for the next decade, long after I left the team. Their coaching philosophy had two tenets. One: every kid, no matter how unathletic, would play in every game, and two: sports should be fun. I thrived in their low-pressure ecosystem; I didn’t mind running around and had decent instincts for teamwork. When the ball wasn’t headed straight towards me, I daydreamed about Nancy Drew, but my distraction was rarely noticed, and never penalized. We had only one extremely competitive, talented player on our team, and the experience was torture for her. I can still picture the fury on her face while our team cheerfully lost game after game. Our fireman-coach offered each of us specific encouragement, and he always said the same thing to me: Ann, try to be a little more aggressive. I nodded in response, the same way I nodded every time a teacher begged me to talk more in class. But I had no aggression in me, and no idea how to summon it. I jogged around the soccer field and remained quiet in the classroom.

I continued to play soccer because my parents insisted I take part in at least one non-reading activity, and because I preferred soccer to other sports. Unless you’re the goalkeeper, it’s rarely your fault if your team loses. I’ve never liked the spotlight, and so it suited me to be one of a swarm of girls on a field. I had a powerful kick; I was good enough to seem like I belonged.

My high school soccer coach, though, hated the very idea of good enough. She was certainly aggressive, and unlike anyone I’d ever known. Diminutive and constantly frustrated, she squatted on the sideline and tore fistfuls of grass from the ground during games. She screamed at us to be more physical, to stop kicking “like girls,” to please, for the love of god, give a damn about winning. Her brand of coaching would likely be frowned upon today, but this was the late eighties, and our parents either had no idea she was screaming at us, or thought it would improve our characters. My teammates and I found her intimidating, but being young girls, we also wanted to please her. The coach’s belief that we contained excellence was intriguing and inspiring. She pointed a particularly ferocious snarl in my direction, and I instinctively understood why: I was the embodiment of good enough. I studied hard enough to be a good student, tried to meet my parents’ expectations so I was a good daughter, and followed every rule set in front of me, to ensure I qualified as a good girl. Was it possible though, like the coach said, that I contained untapped excellence? Was there some deeper truth inside me that I’d papered over with the wrong kind of effort? The coach was holding up a mirror to the person I’d carefully constructed, and for the first time, I questioned what I saw.

During soccer games, I tried—on and off—to be aggressive, but I couldn’t seem to drop my deeply internalized politeness, a trait my coach despised. Each time I collided with a player on the opposite team, I apologized, and my coach tore another tuft of grass. But when I showed up for my senior year season, she fixed me with a look that said: It’s time, Napolitano. She was extra hard on me during practices that fall. She told me that I should be the fastest player on the team, that I should be stronger, jump higher. Every afternoon, I was disappointing her, which meant I was disappointing this mysterious potential inside me. I understood this, and grew jittery. I was scared of missing my last window of opportunity. I didn’t plan to play soccer in college, and I would never again have this small, intense woman’s attention, calling the best of me to the surface. Because of that, I sprinted onto the field at the start of the first game. I stopped listening to the steady stream of thoughts, questions and worries in my head, and instead listened to my body and the rhythm of the game. I was surprised to hear an internal growl when I lunged for the ball. I recognized the sound, though I’d never heard it before. The growl was fierce, and I was different: less friendly, tougher, ambitious. It didn’t occur to me to apologize when I stole the ball from another player, and I ended games streaked with dirt and sweat, entirely spent, and exhilarated. It was my best season, and my coach’s response was one of relief. She nodded at me, in thanks. I had given my all, which was what she’d needed for her own peace. I was amazed at the person I’d revealed myself to be, and satisfied, which were two unfamiliar emotional states for me.

I was never again part of a team, though I wept tears of joy when Mia Hamm, Brandi Chastain, Julie Foudy and the rest of the Women’s National Team won the World Cup in 1999. The unapologetic power of these women, both in their dominant play and in their uninhibited celebration, felt like a dream I hadn’t known could come true. I related to these formidable athletes, perhaps because I was a soccer player, and perhaps because the growl I’d found on that field was still part of my life. I’d recognized, during college, that there was a desire deep inside me to write the fiction I loved to read. I had always written, but with the same lack of intensity I’d once shown just jogging around a soccer field. Now I was aware that I had the capacity for more, and that peeling back the layers inside myself was rewarding work. And when I allowed myself to take writing seriously—no more apologies and no more half-efforts—the growl returned. After all, the stories I felt called to tell deserved my best; throwing away a hundred pages of work that took six months to write was as painful as any athletic failure. The risk involved in writing never stops being real and personally harrowing: what if I can’t write the story as well as it deserves to be told? When that fear veers into despair, I listen for, and rely on, the growl. It reverberates with: this matters, and you have to give it everything you’ve got. The self-doubt is always there, but most days, the growl is louder. It is a gift, and the blank pages in front of me are too.

When I picture my high school coach squatting on the sidelines, screaming at a field full of teenage girls, I hear the question beneath her actual words: Don’t you want to know what you’re made of? What a gift, to have that question rained on us while we were at such an impressionable age. I’m fifty-three now, and I’ve written through everything: enervating illness, rejection letters, day-jobs, toddlers and teenagers, books that sold well and books that didn’t. There is one theme I find myself writing to over and over again, and it’s how to live a meaningful life. I keep trying to do so myself, as unapologetically and fiercely as possible. Isn’t that what it is to be ambitious?

Your prompt for the week:

Write about what you’re made of—about the excellence you contain. Who or what showed this to you? What does it impel you to do or to make?

If you’d like, you can post your response to today’s prompt in the comments section, in our Facebook group, or on Instagram by tagging @theisolationjournals. As a reminder, we love seeing your work inspired by the Isolation Journals, but to preserve this as a community space, we request no promotion of outside projects.

Today’s Contributor—

Ann Napolitano is the New York Times bestselling author of Hello Beautiful, the 100th selection for Oprah Winfrey’s book club; Dear Edward, a Read with Jenna selection and an Apple TV+ series; A Good Hard Look; and Within Arm’s Reach. For seven years, Napolitano was the associate editor of the literary magazine One Story, and she received an MFA from New York University. She has taught fiction writing at Brooklyn College’s MFA program, New York University’s School of Continuing and Professional Studies, and Gotham Writers Workshop.

For more paid subscriber benefits, see—

On Failure, a video replay of my Studio Visit with my husband Jon, where we talked about “getting your rejection in” and how if you’re not failing you’re not trying, and we shared his ma’s red beans recipe

Read Me, See Me, Like Me, an installment of my advice column Dear Susu, where I answered a question from a reader who feels the urge to write but isn’t sure how to share her words with the world

A Creative Heart-to-Heart, a raw, unfiltered conversation with Jon where we talked about how we get into a creative flow, practice as a form of editing, and how we use a creative practice to we marry our joys and sorrows

Pre-order The Book of Alchemy—

My new book, The Book of Alchemy, comes out on April 22, 2025. I’d be so grateful if you would preorder a copy for yourself or a friend. Preorders are so important for authors, and it would mean everything to me!

I took a poetry writing class in in eighth grade. I really enjoyed the class. I wrote a few poems when I was in an arts’ camp and on and off throughout high school. After that I forgot that I liked to write. During the pandemic, I was working in the hospital while most people were at home. I realized I needed a way to express my emotions and I came back to writing. About a year after it began I learned about the Isolation Journals. I started to respond to the prompts. For the first year I never shared my writing with the community. It felt too personal and I didn't feel I was good enough. Now I share almost every week and people are very encouraging and kind. At the same time as I started to respond to IJ prompts, I discovered Narrative Medicine and began to participate in their rounds whenever I could. In those meetings you have only four minutes to write.It is a much smaller group than the Isolation Journals’ community and I started to share my work there. I received positive feedback which made me more open to showing others my work. On my own which I found that there were patients and situations that really touched me and I felt that I had to honor their stories. I wrote about them and also about my self.

I showed some people a poem I wrote about a patient who froze to death and they encouraged me to try to get it published. I sent it out to one journal who rejected it, but a second one liked it and it will be published this month in an academic journal. The success of the first poem has emboldened me to try with another.

Recently I started to participate in monthly poetry workshops with a different poet every month. Even though I work a full time job with very long hours (about to go to work in a few minutes) I realize that if something gives you joy you can find time to do it and it even makes it easier to get through the work day. In last month’s poetry workshop with Joseph Fasano he described the need to write as what he imagines an oyster experiences when it has an irritant in its shell and needs to form a protective coating which creates a pearl. An oyster cannot rest until the pearl is formed and neither can I when I have something to say.

Dear Suleika, the most joyous news, to have your loves by your side. I only hope to be across the seas—to sit in the hush before the lights dim, to feel the charge in the air as words take shape, to witness the alchemy of it all.

I hesitated before writing it.

A name badge, a blank space, a sharp-tipped marker waiting in my hand. I could have used the name I had long hidden behind—the small one, the soft one, the one that asked nothing of the world. But instead, I wrote my own. The real one. The one I had avoided, misplaced, allowed to shrink.

Later, a woman I admired glanced at it & smiled. "A beautiful name," she said, tracing the letters with her eyes before looking at me. "It could be from anywhere. A name that carries distance. History. Like a face that belongs to many places at once."

A compliment that settled, in a way I’d not felt before.

For years, I did not place my name on the things I made. Not on my images. Not on my work. Not on the small, careful moments I offered the world. It was easier that way. To remain at a distance. To let the work exist without pointing back to me.

I had a name once, not the one given to me but the one I was shrunk into. A childhood nickname—something soft, something small, something that fit inside the narrow space I was allowed to take up. It followed me longer than it should have, long after I had outgrown it. I used it without thinking, signed emails with it, introduced myself that way, as if I were still trying to fit into the version of me they had made.

There is safety in the background. In quiet observation. In being the one who sees, rather than the one who is seen.

But something shifts when you name yourself.

To write is to place myself inside the frame. To step forward. To take the weight of my own voice & let it stand.

It is a small thing, & yet—

It is not.

Because a name carries history. Mine carries the weight of doors shut behind me, of hands that let go, of a family that has not spoken my name in years. But still—it is mine.

And I am here.

With thanks also to Ann for her words, which met me at exactly the right moment.