Hi friend,

Five years ago this week, as we were all adjusting to the new realities of quarantine, I started a newsletter called the Isolation Journals. It was a reprisal of a daily creativity project I had done during my first bout with leukemia a decade earlier that had allowed me to alchemize a time of sorrow and isolation into something connective and generative. The premise was simple—each day, we would read a short essay and creative prompt, then journal together. A friend who was helping on the project asked me, “How many people do you think will sign up?” I shrugged and said, “Maybe a few hundred?”

When I sent out the first prompt on April 1, 2020, the number had reached 20,000, and the day after that, 40,000. By the end of the first 100 days, over 100,000 people from all over the world had joined this creative community. I remember being awed by the multitudes, but I quickly came to understand the reason why the Isolation Journals took off is the same reason that it continues to grow—why there are more than 200,000 of us now. It’s because cultivating a creative practice forges a sense of connection, a call and response, reverberations begetting more reverberations. It’s how, in the stories you share here, I recognize myself. How that reflection makes me feel a little less alone.

If you’ve been here from the beginning, you may remember the very first essay and prompt I sent out was called “Letter to a Stranger.” In it, I wrote about how in my childhood journals, I often tacked a name at the top of the page, to imagine a person on the other end. “It’s often easier for me to start or to get unstuck when I conceive of writing as having an addressee,” I wrote. “It helps me say what I want to say, to fall into a more natural, conversational rhythm without overthinking.”

When people began sharing their responses that day, I remember being blown away by the openness, the vulnerability, and the beauty in these gorgeous missives. One journaler wrote to the security guard at the hospital where she worked. One wrote to her estranged father. One wrote to the cardinal outside her window. Another to his yet-to-be-met future wife.

But the letter that moved me most deeply was penned by a woman named Jennifer Leventhal whom I had never met, but whose daughter Danielle was known to me. A few years earlier, I had bumped into Danielle in a cafe in New York City. A fellow cancer comrade, she recognized me from my New York Times column and had come up and introduced herself. Later, we connected online, and even later, she painted a portrait of my late beloved scruffy terrier mutt, Oscar, and me.

When “Letter to a Stranger” went out five years ago, Danielle was in treatment for a relapse of a rare sarcoma. In response to that first prompt, her mother Jennifer wrote to another mother she had encountered in the hospital waiting room, a woman she’d given an egg-and-avocado sandwich to—a simple gesture that came to mean so much more.

Jennifer’s letter changed my relationship to the waiting room and the people I encounter there. It has made me gentler in my knee-jerk assumptions and more generous with my own small gestures, even if its just meeting someone’s eye and smiling. I still have never met Jennifer in person, but she’s not a stranger. She is known to me. I think of her every time I’m in a hospital waiting room. Every time I see a mother with her child. Every time a patient pulls out a sandwich.

I continue to marvel at the way these stories resonate, how they circle back in rhymes. I wrote a column that Danielle read. She later painted a portrait of me, which I gifted to my own mother, which her mother Jennifer gathered into a book after Danielle died. Danielle’s book of paintings now sits on my shelf, and I can turn to it any time. I marvel at how I sent out that first prompt, and Jennifer penned a profoundly moving essay that was one of the first that came to mind as I was conjuring up The Book of Alchemy and will soon appear in its pages. Now I’m sitting in those same hospital waiting rooms with my mother, and using words and watercolors to navigate my own recurrence, thinking of Danielle and Jennifer and their beautiful words and watercolors. It’s all rhymes—and that to me, is the magic of living a creative life. You’re not just muscling through the days without looking up. You’re paying attention to the mystery of our time here and the magic of our intersections and encounters with one another.

The paradoxical nature of this project is that journaling is something we think of as solitary, something you do in the privacy of your notebook. It’s just you and the page. But what continually surprises and moves me are the connections we make as a result. It reminds me of what I learned during my first 100-day project: that if you’re in conversation with the self, you can be in conversation with the world.

And so today, in honor of our fifth anniversary, I want to return to the beginning. Below you will find Jennifer’s essay and our very first prompt, which asks you to write a letter to a stranger. It’s a powerful exercise, one that is instantly transformative—because when you write to a stranger, they cease to be a stranger. They become known.

Here’s to many more years of becoming more known to ourselves and to each other through the page.

Suleika

This week we’re celebrating the fifth anniversary of the Isolation Journals. Thank you for being a cherished member of this community. If you value this work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. This newsletter is a reader-supported publication, and paid subscriptions make possible everything we do.

Prompt 331. Letter to a Stranger by Jennifer Leventhal

Dear Mother in the Waiting Room at MSK,

I’ve been thinking about you and your son for over a year. We were sitting on couches facing each other, me with my young adult daughter’s balding head propped against my shoulder as she took a few bites of her egg-and-avocado sandwich. You with your teenage son’s curly head nesting in your lap as he slept.

You smiled shyly, leaned forward, and whispered, “Where did you find that breakfast? I can’t get him to eat anything.” Suddenly, I felt validated, like maybe some of the random tidbits I’d learned over the past two excruciating years might actually be helpful to someone else.

“Eggstravaganza,” I whispered with a little too much excitement. “It’s a breakfast food truck just two blocks away, next to St. Bartholomew’s Church on Park Avenue.”

“Is it expensive?” you whispered back. I had to check myself before replying. It was an egg sandwich, and I would have paid anything if it brought some nourishment and a few minutes of pleasure to my frail daughter.

“I have an extra in the bag, and I don’t want it to go to waste. Please take it.”

Your eyes fell to the carpet, but you mumbled, “God bless you, thank you so much,” as you reached for my lunch.

I looked away and tried not to listen when a social worker came and sat by your side, but that was impossible. I overheard her ask if you had any trouble getting to the hospital without a car, then suggest the “Access-a-Ride” program. She said she had made you an appointment with the Finance Assistance Office, who could help families who were uninsured. I stole a glance at your sleeping son, tall and lanky but with the face of a child, and I felt ashamed of all the times I had felt sorry for our family during this unending war against cancer.

It was and continues to be inconceivable to me that you had to face such an insurmountable battle without the resources I took for granted. I wanted to hug you and tell you three things—that you were doing your absolute best for your boy, that you were in the best possible place for his care, and that everything would be okay. But I sat motionless, unable to comfort you. I knew the first two were true, but not the third. None of us sitting in that waiting room—that club no one ever wanted to join—none of us could know if everything would be okay.

Your prompt for the week:

Write a letter to a stranger—someone imaginary, someone you met once, someone you only know from a distance. Tell them any and everything: when you first noticed them and what has happened since, how you’d like your day to start or to end, or what’s been on your mind. Or tell them a story about a time when something difficult led you to an unexpected, interesting, maybe even wondrous place. Say whatever you want to say, whatever you think they need to hear.

Today’s Contributor—

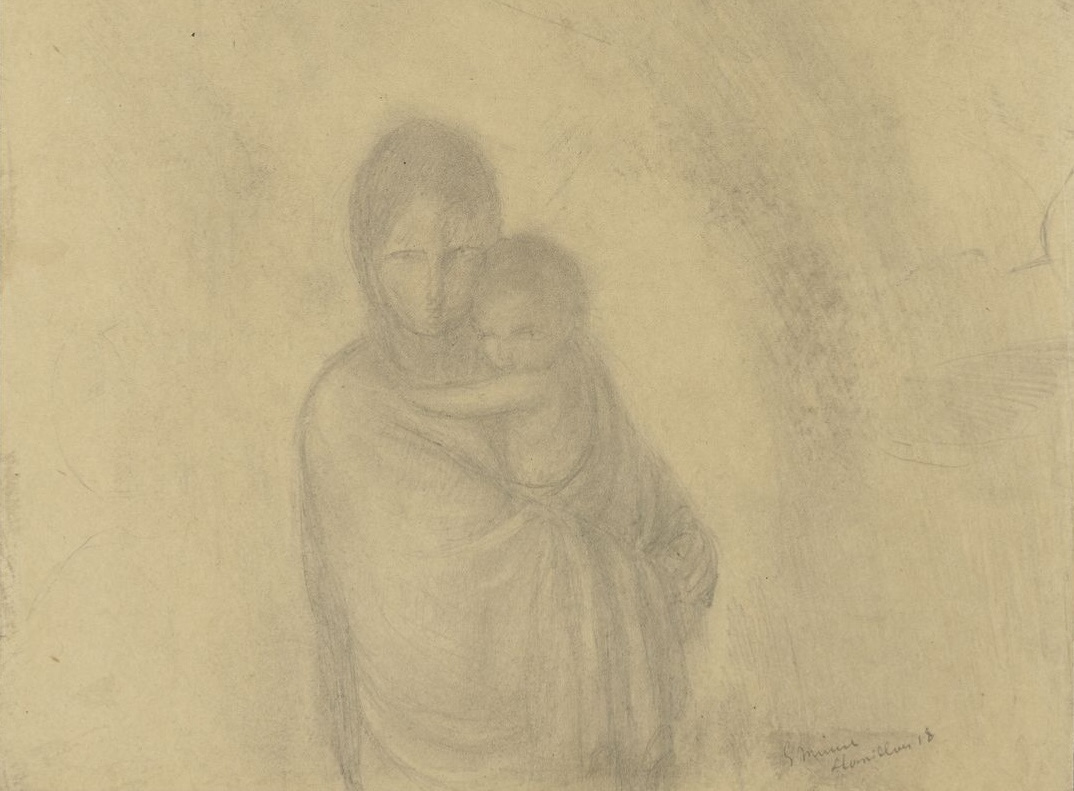

A former magazine editor and communications consultant, Jennifer Leventhal is a caregiver advisor with the Patient and Family Advisory Council for Quality (PFACQ) at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. She lives in Rye, New York, with her husband, Eric, and their doodle, Hudson. She is the proud mother of Alex and Danielle, who passed away in 2021 at the age of twenty-seven. Jennifer is pictured here with Danielle and Hudson.

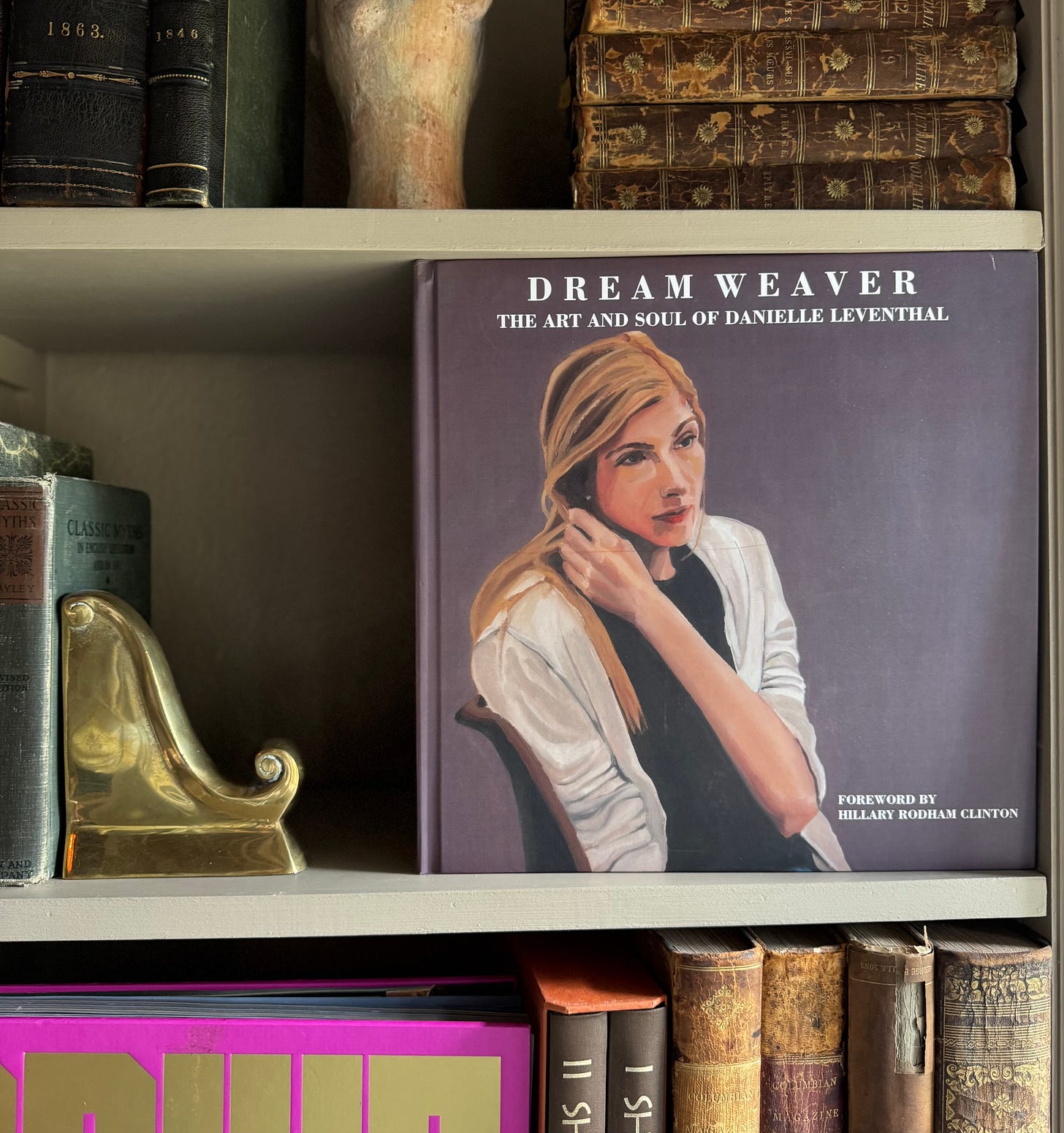

All proceeds from the book of Danielle’s paintings, Dream Weaver, goes to First Descents, an organization that organizes outdoor adventurers for young adults with cancer that’s near and dear to both the Leventhals’ and Suleika’s hearts. You can get yours here.

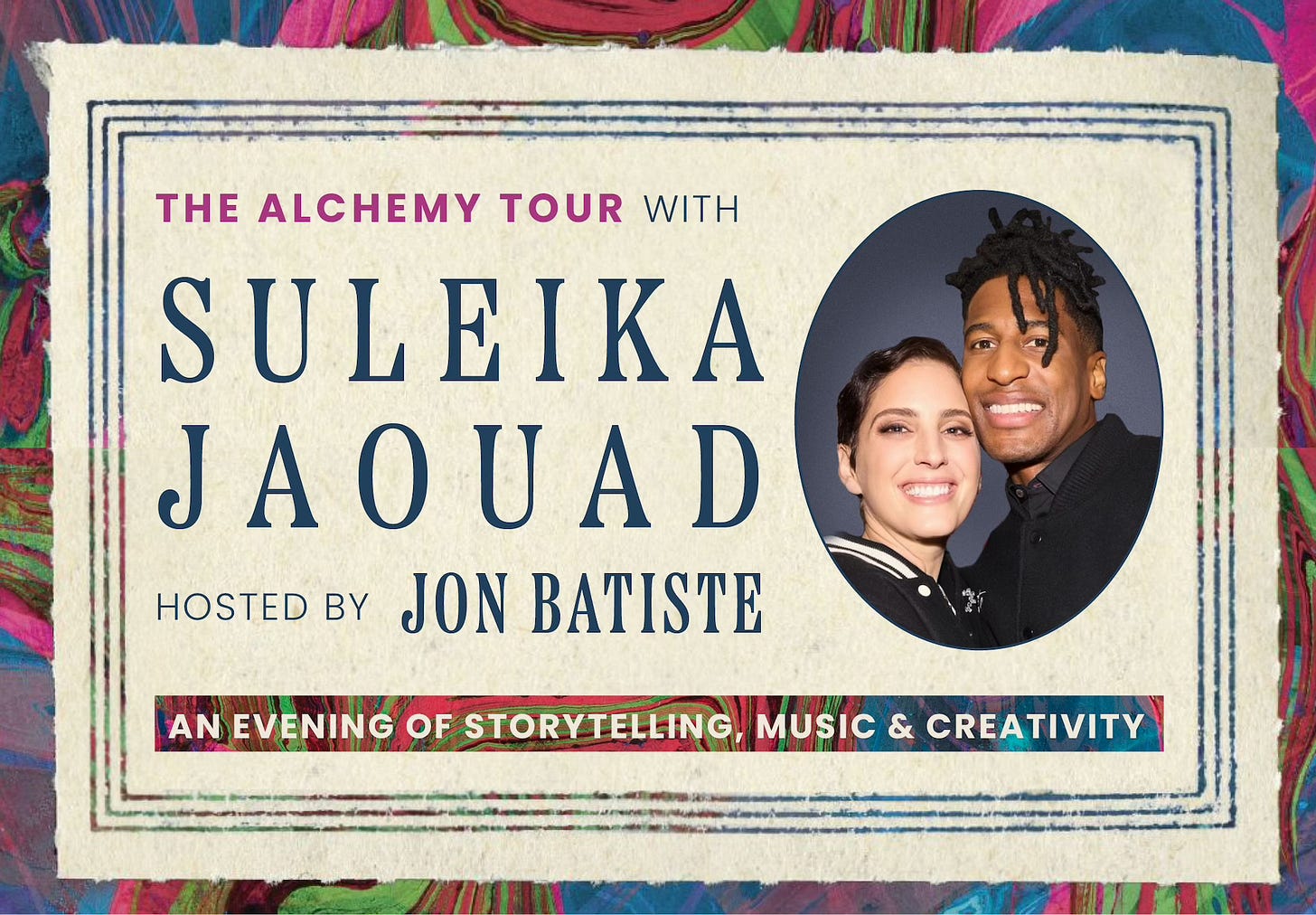

Some Exciting News—

Based on the incredible response to the Alchemy Tour, we’re thrilled to be adding more dates—to start, we have one in Minneapolis and a second in San Francisco! I’ll be sending an email with links to buy tickets on Thursday, April 3, at 12pm ET, so keep an eye on your inbox!

A quick reminder: There are a few seats left in Philly and LA, so snag them while they last! Each ticket comes with a signed copy of the book. You can find more info here.

Your soul-stirring testament to the incredible power of attention, of story, of showing up… with a pen, with a sandwich, with a gaze that dares to see moves me. Five years on, and this project feels less like a newsletter and more like a living archive of human tenderness in all its complexity: its ache, its art, its alchemy. You’ve made the private act of journaling into a public gesture of solidarity, turning solitude into communion. That is no small feat, and I think I might write in the name of many: thank you!

The way you describe the echo of one small encounter reverberating through years, bodies, losses, and art, it reminds me of Rilke’s line: “Everything is gestation and then bringing forth.” These letters, these prompts, these stories, they have gestated in hospital waiting rooms, in grief, in the long shadow of illness and the fleeting light of joy. And still, they bring forth something astonishing: connection without spectacle, empathy without pity, beauty without pretence.

Thank you again for creating a space where the stranger is never truly a stranger, and the page is never truly blank. This work is sacred. It matters. And it endures.

I’m looking forward to your book. For the past four weeks, we have known that my mother has terminal colon cancer. For a week now, she has been battling an infection that entered through her port, and she is growing weaker by the day. I wish I could find the words to express my feelings, to write them down, but I don’t know where to start. I truly hope that The Book of Alchemy will help me process my grief on paper.

Thanks to your essays, I am more present in these moments by her bedside. I take in everything—the sunlight filtering through the curtains, the heaviness of her breathing, the brief smile when she opens her eyes for a moment. Your words help me absorb these final days with my mom more fully. I am grateful to you.