Prompt 312. The Olive Oil King & Nosf-Nosf

& the artist Diana Weymar on what we can make from the past

Hi friend,

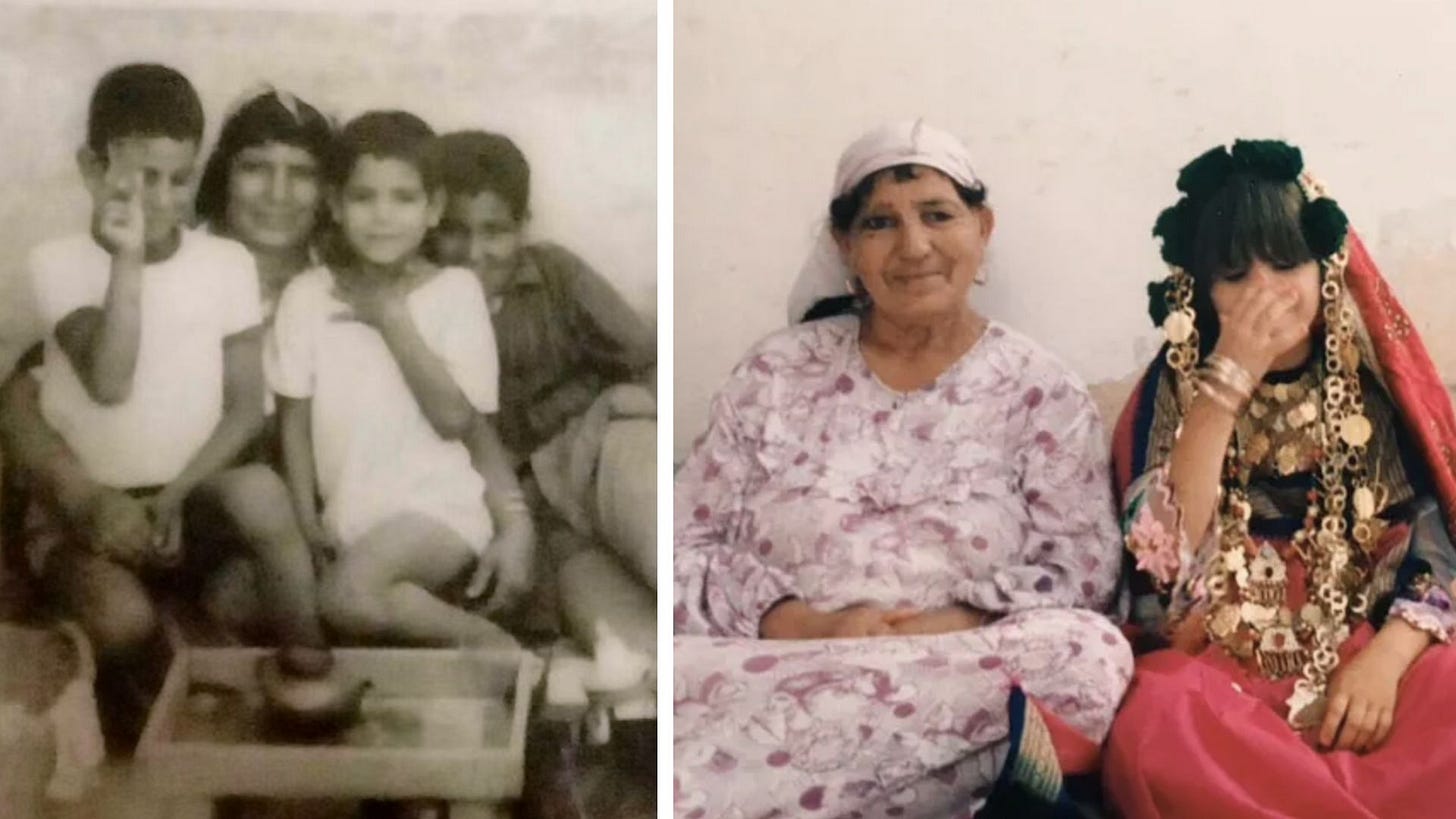

Recently I’ve been spending a lot of time with my dad. My mom and brother are currently in Tunisia, so Papa Hédi’s been coming down to stay with me about every other week to drive me to treatment and for the general company. My dad is a man of habit and routine. He starts every morning by swallowing a spoonful of olive oil—good for digestion, he says—and he also uses it as moisturizer and mouthwash. Really he thinks of it as a cure-all, which is why I call him the Olive Oil King.

Hédi comes by his “olive oil as cure-all” belief honestly—when he was young, his mother used it to treat all kinds of maladies. In his memoir-in-progress, Until the Sahara Blooms, he writes about how, as a child, on a very cold, very dark winter night, he was shaken from deep sleep by a searing pain in his ear. He lay whimpering in bed, hoping his mother, whose bedroom was across the courtyard, would hear him. Soon she appeared in his room with a heavy blanket wrapped around her shoulders, “like an angel of mercy,” he said. She asked him what was wrong, then headed to the kitchen and returned with a thimble full of warm olive oil. She poured it in his ear, the pain went away, and he quickly fell back asleep.

Only a little while later, the pain returned, mild at first, then worsening. Eventually, Hédi woke his younger brother up and asked him to fetch their mother again, which his brother did reluctantly, given it meant going out into the courtyard, into the cold. His mother returned, knelt beside him, and murmured, “Nosf-nosf,” meaning “half-half” or “fifty-fifty.” It was shorthand. She was saying, “I can’t take all your pain, but let me at least take half.” Then she rested her cheek on his cheek. Hédi immediately fell sound asleep and didn’t wake until morning, the pain gone but the memory of her tender care indelibly inked in his mind.

Because Hédi has shared this memory with me, it’s also inked in mine. So when we were at the hospital earlier this week waiting to see if I was cleared for chemo, and I was feeling awful—nauseated, tired, and generally just down—and my dad put his hand on my head and said, “Nosf-nosf,” I was transported. With that tiny phrase that means nothing to anyone else, I felt his hand and my grandmother’s hand at the same time. It’s such a hard thing to watch someone you love suffer, knowing you can’t actually fix it for them. (Not even with an endless supply of olive oil.) Still, my dad’s words were a balm. Not only was I not alone in my suffering, I knew beyond a doubt that if it were possible, he would take my pain. His empathy lightened my burden, the same way his mother’s had on that cold night.

What we make of the past—and how it can echo in the present—that’s the subject of today’s guest essay and prompt. It’s called “The Handmade Tale” by Diana Weymar, the artist and author of the book Crafting a Better World: Inspiration and DIY Projects for Craftivists, to which I contributed an essay. May it inspire you to revisit old memories, and to fashion from them something new and beautiful.

Sending heaps of love and olive oil,

Suleika

An Item of Note—

A quick reminder that our next meeting of the Hatch, our virtual creative hour for paid subscribers, is happening today—that’s Sunday, November 17 from 1-2pm ET. Carmen Radley will be hosting this time, sharing a favorite poem and a spiritual practice to awaken compassion. Find everything you need to join us here!

Prompt 312. The Handmade Tale by Diana Weymar

Every sentence I write begins with a capital letter and ends with a period. Every line I stitch starts and ends with a knot. Between those two tight knots, the thread weaves through the fabric, following the movements of the hand and the stab of the needle. A lot can happen between those two knots: a word created, a heart broken, additional knots formed if the thread is too long, images embedded in the weave, a story told, and a trail left behind. Markings are made. Metaphors abound.

One of the stories I tell now with thread and textile is that of my childhood, but it wasn’t until my mid-forties that I found the right medium to bring it to life. I wrote short stories about my childhood in college, but as it turned out, it was still too fresh, too early for me to tell the story. Later I worked in publishing and film, and again I was focused on storytelling, but this time I sat on the sidelines like a story-telling doula, ready to birth other people’s stories onto the page or screen. I liked this. It was deeply satisfying to be adjacent to the main event, to watch how others did it. I traced their threads with my fingers, memorizing the tricks, turns, stitches, approaches, and styles. I noticed patterns. I saw things I recognized and things I had never seen before.

But sooner or later, in some form or another, we all return home to our own stories. My path home began in 2012, when I took a course called “Art and the Language of Craft, Textiles and thread would eventually take me, quite literally, around the world, but first, it took me back to where and how I lived from the ages of one to eight: in the wilderness of Nothern British Columbia. My parents built a log cabin and dogsleds and riverboats. They planted gardens, fished with large nets cast out into the river, hunted wild animals, made tools, and sewed clothing.

For my class I studied photos of this time. I looked at them, wondering who I was back then, and they looked back at me, wondering who I was now. Eventually I could see the first knot: my childhood was a starting point from which I could anchor myself to move forward to tell my story. I picked up a small, cotton dress that had belonged to my mother when she was less than a year old. I threaded the needle, tied a knot, and started stitching a photo. I started to recreate my past by hand.

In this photo, my father is standing next to a moosehide he is tanning. Every moose has enough brains to tan its own hide. His words come back to me as I stitch, as does the way he would sit on a wooden stool with the hide stretched out on a frame in front of him and the sound of the scraper on the hide. I am wearing a stiff blue wool jacket sent to me by my grandmother in Connecticut. It was uncomfortable, more like a straightjacket, and made it almost impossible for me to bend my arms. I scowl at the camera because I am looking into the light. I remember that too. In my right hand is the handle of a wagon that was never too far away. Red metal wheels that were stiff so that I half-dragged it as I pulled it. I am giving my doll a ride. She was, most likely, my best friend at the time.

As I stitch my past, I remember. (I am still remembering when I stitch.) This is my needle to thread, and no one can stitch this story the way I do.

I have been asked if I make my work by hand. I reply that my work is to make by hand.

Your prompt for the week:

How do you preserve and explore the stories of your past? Do you bake cakes that help you remember? Cook from family recipes? Make something new out of old family textiles? Are there metaphors in your practice that bring you closer to actual experiences? What do you weave when you pull on the threads of your life?

If you’d like, you can post your response to today’s prompt in the comments section, in our Facebook group, or on Instagram by tagging @theisolationjournals. As a reminder, we love seeing your work inspired by the Isolation Journals, but to preserve this as a community space, we request no promotion of outside projects.

Today’s Contributor—

Diana Weymar is an artist and activist. She grew up in the wilderness of Northern British Columbia, studied creative writing at Princeton University, and worked in film in New York City. She is the creator and curator of Interwoven Stories and the Tiny Pricks Project, both of which are open for public participation, and the author of the book Crafting a Better World. Her work has been exhibited and collected in the United States and Canada.

For more paid subscriber benefits, see—

To Betray or Not to Betray, an installment of Dear Susu where I answer the question “How do I write my story without hurting the people I love?”—and share my good-faith protocol for writing about others

On Writing Yourself Home and Whole, a video replay of my Studio Visit with the memoirist Nadia Owusu, where we talked about journaling as creative source material, writing your way through trauma, and how memoir can be a radical act of reclaiming the self

Behind the Scenes of American Symphony, a video replay of my conversation with my husband, Jon Batiste, and Matt Heineman, the director of our Oscar- and now Grammy-nominated documentary, where we talked about peak compartmentalization, learning to say “I’m not okay,” and how Matt squirreled his way into filming at the Grammys

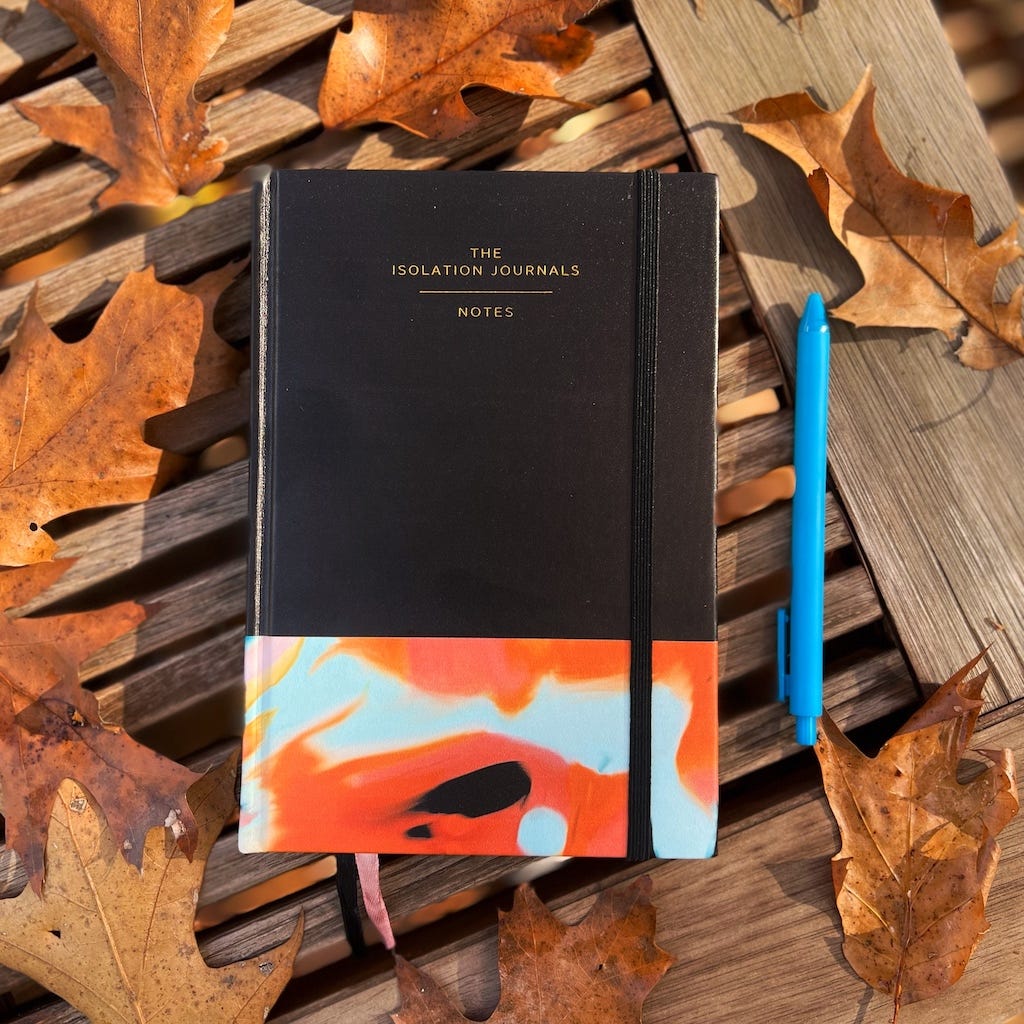

Our Isolation Journal No. 1—

If you’re looking for a fresh start for fall, treat yourself to our custom journal! It has all of our favorite features: the perfect size to tote around wherever you go, ink-bleed proof paper, and numbered pages for easy indexing—and for extra inspiration, we printed our Isolation Journals manifesto on the flyleaf. Get yours by clicking below!

A tear drips olive-oilily down my cheek.

What a tender moment. Dads. Just, dads. My heart, my heart. I am living with stage 4 lung cancer. A cancer lifer. This touched me. How they would give their life to take our pain away?

Half, half. Yes, yes.

Thank you from my delicate heart for sharing.

A smile from London to you.

💛🩷💜💚❤️🧡💙🩵🤍🩶

Hello. Thank you for a beautiful story of your father and culture and traditions. And again being vulnerable to share your journey of chemo and health. I grew up with Greek and Italian grandparents and still visit family in both countries. So many traditions I have that remind me of your share. What I also relate to is my husband from Germany who comes to all my doctors visit and procedures and more. And wants to take the pain away. I had tears with these words" It’s such a hard thing to watch someone you love suffer, knowing you can’t actually fix it for them. (Not even with an endless supply of olive oil.) " And loved these words "Still, my dad’s words were a balm. Not only was I not alone in my suffering, I knew beyond a doubt that if it were possible, he would take my pain. His empathy lightened my burden" With much love for your dad and you.