Prompt 291. What Breaks & Remakes Us

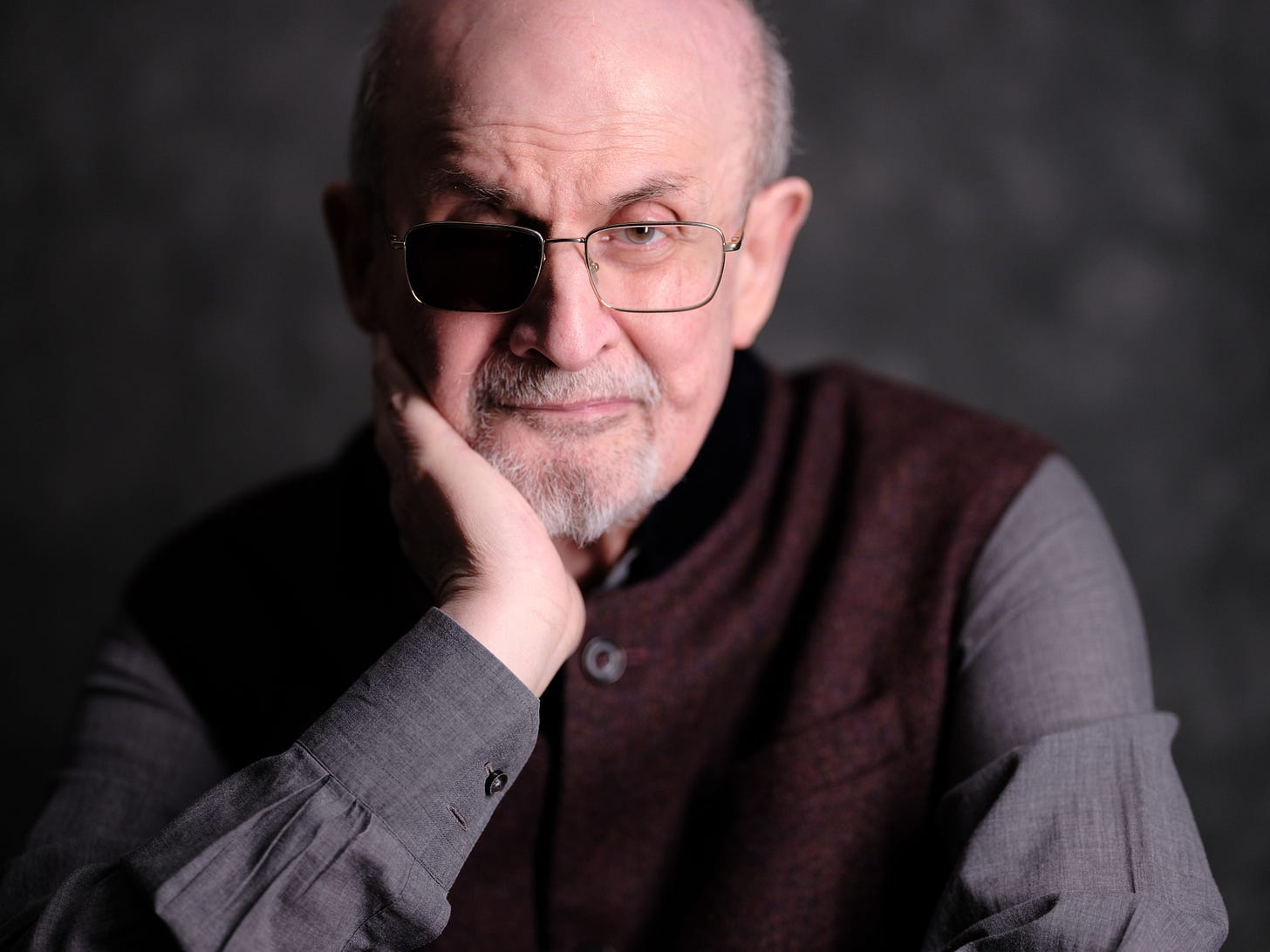

Salman Rushdie on calamity and consequence

Hi friend,

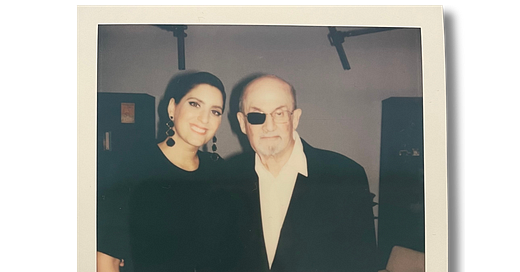

Last week, I had the incredible honor of sitting down with the world-renowned author Salman Rushdie to talk about his stunning new memoir Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, which comes out in just a couple of days, on April 16 (along with a recording of our interview). The book is his reckoning with the attempt on his life thirty years after a fatwa was ordered against him. Not only is it an incredible read, it’s also a poignant example of the power of words and of meeting violence with art.

I’ve been reading Salman’s work since I was a teenager and have long admired him both for his writing and for his advocacy around free speech principles. So I was very excited—and equally nervous—about this opportunity to talk to him about his beautiful book. In our conversation, I brought up that old Hemingway saw, the one about how the world breaks you, but afterward you’re stronger in the broken places. "I agree," he said, "but only with the first part.”

Knife is the sixteenth book that Salman has written since the fatwa, and he composed it with one eye and one hand while in the throes of PTSD, meaning that his brain was, as he put it, all “blankness and junk.” Those are the kinds of obstacles that might leave someone so discouraged they give up altogether, but he kept at it, and he slowly found his way back not only to the craft but to himself. When I asked Salman about why he continued on, he said that if he hadn’t kept writing, then the assailant would have succeeded in killing him, even though he would still be alive.

In my work, I have long been interested not in the calamitous events that befall us, but in how we respond to them. Like Salman, I think the first part of the Hemingway saw is undeniable. The world will break all of us in some way—big or small, physical or mental, when we’re young or old, or all of the above. But becoming stronger in the broken places doesn't happen automatically. Some reckon with their calamities in a way that leads to newfound strength and post-traumatic growth. Others become embittered, eyeing the world with distrust and fear. Some get lost in between.

My own calamity taught me this—and continues to teach me this. When I was first diagnosed with leukemia, people often called me “inspiring” and “brave,” and that always chafed. There are things I’m proud of, that I believe were brave, like caring for my friend Anjali, who had the same disease I have, and sitting vigil with her as she took her last breaths. Like embarking on my road trip at a time when I was new to driving, when the whole world seemed terrifying. But to me, there doesn’t seem to be much inherent merit in the mere act of surviving, especially something you didn’t choose. It’s the same reason I struggle with the battle metaphors, and why I cringe when I see headlines about some person “losing their fight” with an illness. I have many friends who were far braver and stronger than me who did die. More often than not, whether we survive has nothing to do with our bravery. So much of it is chance.

It’s only in the aftermath of a calamity that bravery comes into play—in how you respond, in how you take agency, in the meaning you make of the calamity. It’s what you create from it, how you continue to show up for yourself and for others, and whether you keep an open heart despite being hurt, despite the impulse to protect yourself from more pain, more loss. That’s when the second part of the Hemingway quote comes in—that’s becoming stronger in the broken places.

In a way, I feel so fortunate to have met Salman at this particular juncture in his life—though of course, I wish the event that led him to write this book had never happened. There was a palpable humility and gratitude and a sense of clarity emanating from him that he himself says is a response to what happened. To meet brutality with that kind of grace leaves me in awe. It brings to mind another quote from Hemingway: “Courage is grace under pressure.”

Today, it’s my great honor to share an original essay and prompt from the great Salman Rushdie, written especially for the Isolation Journals. May his words and his example remind us that the world will break us with all kinds of calamities—but if we survive them, we have a choice in how we respond.

Sending love,

Suleika

Some items of note—

My interview with Salman Rushdie will be available on Tuesday, April 16 at 8 p.m. ET on Vimeo. I’d like to invite you to join us for this intimate conversation on loss, love, the power of art, and finding the strength to keep going. You can get access to it with the purchase of Knife, which I highly recommend! Find all the details here.

It felt so resonant to be in conversation with Salman on the heels of last week’s Studio Visit, where I shared about the struggle to do the work I love most while living in a body that doesn’t always cooperate. I also got to talk about some of my favorite things—my dogs, of course, and how I find creative inspiration and the way painting has forged a meaningful new layer of connection between my mom and me. If you missed it, you can find a video replay here.

Our next meeting of the Hatch, our virtual creative hour for paid subscribers, is happening next week—that’s Sunday, April 21 from 1-2 pm ET. Carmen will be hosting this time, meditating on a poem that echoes one of my husband Jon’s favorite sayings: “I love you even if I don’t know you.” To mark your Google calendar, click here!

Prompt 291. A Sundering by Salman Rushdie

For many years now, I have taught a nonfiction graduate seminar at New York University. In several of the books we read and discuss, a common theme emerges. People in a peaceful community—often a remote, rural place—are suddenly confronted with a calamitous intervention into their lives. Two examples of this are Truman Capote’s true-crime novel In Cold Blood, and Svetlana Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl. Capote has said that when he first read about the murders of the Clutter family in Holcomb, Kansas, a small town at or near the very center of the United States, he was more interested to discover the effects of the murders on the people of Holcomb than he was in the crimes themselves. Meanwhile Alexievich, for obvious reasons unable to examine the site of the exploded Chernobyl nuclear reactor itself, and unable to talk to all those first responders who died in the effort to shut it down and make it safe, talks instead to the survivors, and constructs the story of the horror through their traumatized voices.

Capote arrived in Holcomb, accompanied by his childhood friend Harper Lee, to find a community mired in mutual suspicion. Until the arrest of the actual killers, who were strangers from far away in search of money, the townspeople of Holcomb mostly assumed that the murderer was one of them. They began to eye one another with distrust and even fear. Some Holcomb people moved away. The town no longer felt safe.

The Chernobyl survivors found themselves treated with fear by their fellow countrymen, much as the survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear bombs had been treated in Japan. People didn’t want to come near them, let alone marry them or bear their children. And many of them decided that the only way forward for them was to return to their homes near the reactor, knowing full well that radioactivity levels in the region were off the charts, so they would be drastically shortening their own lives by going back.

We all have a picture of the world, an idea of what is real, inside which we live. Sudden disaster—the death of a loved one, the loss of a vital job, a murder, a meltdown at a nearby nuclear reactor—breaks that picture and we have to try to reconstruct it, or something like it, or something completely different.

I myself have had such an experience, when I was attacked by a man with a knife in August 2022 and almost killed. It has taken me a year and a half to deal with the physical and psychological consequences of that attack, and perhaps I haven’t fully dealt with it even now.

Your prompt for the week:

Write about an event that changed your world, or the world of someone close to you, that forced you to re-examine your beliefs. Or, do it as fiction. Imagine a peaceful suburban community, disrupted, one morning, by the landing of a flying saucer in the town square. In fact or fiction, write about an event that disrupts reality, and the human consequences of that event.

If you’d like, you can post your response in the comments section, in our Facebook group, or on Instagram by tagging @theisolationjournals. As a reminder, we love seeing your work inspired by the Isolation Journals, but to preserve this as a community space, we request no promotion of outside projects.

Today’s Contributor—

Salman Rushdie is the author of fifteen novels and one collection of short stories. He has also published five works of nonfiction and coedited two anthologies. He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and a Distinguished Writer in Residence at New York University. A former president of PEN American Center, Rushdie was knighted in 2007 for services to literature.

For more paid subscriber benefits, see—

Heartbroken Friend, an installment of my advice column, Dear Susu, where I write to a reader about living after the loss of a friend

Notes from the Hatch: Eleven Minutes, a recap and transcript of a pinch pot practice with ceramicist Rhonda Willers that deepens gratitude and clears the way for creativity

Creating Beyond Fear, an interview about facing our doubts with the dazzling and brilliant Elizabeth Gilbert

I can still remember the words that drew a line in the sand between before and after, ‘by the time you read this, she may have already left our shores.’ I remember crying and I remember not really understanding, a child myself just like my friend. 12-year-olds aren’t meant to pass, but she did, and my belief that I was invincible shattered — but that didn’t make me crumble, it made me stand taller. I began to see stars more clearly, I heard birdsong every morning and evening wherever I went, I started to stand outside at dusk and thank the world for another day. My understanding of death was limited, but as I grew I began to grapple with it more. It would have been easy to get angry and stay that way, but what mostly happened was my belief in the beauty of the world strengthened. I saw, and still see the glorious nature of little things everywhere. Her passing sent ripples through our small town but the ripples were of kindness and love that she had created and they continue to reverberate even now. My belief of what happens after death changed. I believe she is woven into the flowers planted over her grave and into the wind that makes the trees whisper and in the stars that shine light to guide me. Though she may have left these shores, she has shown me everyday to look around with intent, admiration and wonder.

And thank you every week for sharing wonderful words that help us see the world in a new light! 🌱💛

I loved my life in Brooklyn, and living in a 6th floor walkup. I was grateful to have the opportunity to support many young people's dreams. I wanted to give back, and when the opportunity came to start a program in another city, I took a chance. My learning center was left in another's hands. The program that I started was really good but the funding source left. The work was too difficult. My program in Brooklyn was run to the ground. My apartment was usurped. I was close to 60, had nothing but an old Honda, a dog and the school cat. I started anew, and thankfully had a position. Several of my students got shot--I held on eventually planted gardens and watered the lives of many. The brokenness remaned, family disappeared-dogs remained- I mean hurt remains, recalling is painful--I take responsibility for my choices--knowing some were based on hopefulness of a different outcome. I know where the cracks were way back in a childhood that was dark-however-being of an optimistic nature- I am still listening.