Breathing Out

Day 4 of our 30 Day New Year's Project: On breath as ritual & Sarah Ruhl on haiku

Earlier this week, I wrote an essay arguing against New Year’s resolutions. This was not, as it turned out, a preventative measure. The gravitational pull of January—the insistence that one might, with sufficient will, step cleanly into a better self—proved nearly inexorable.

On New Year’s Day, less than seventy-two hours after the essay went live, I found myself in the Notes app on my phone, drafting a list of ambitions that bore a striking resemblance to the very thing I’d just warned against. Finish my next book. Mount a solo painting show. Start a podcast. Convert the house to solar power. Text personal-trainer friend to ask how to ease back into working out after a three-year hiatus from any and all forms of exercise. Adopt two miniature donkeys. Rest (???).

I wasn’t calling them resolutions. The list lived under a heading titled Big Picture Goals: 2026, which felt like an important distinction—possibly a loophole. But my body was unconvinced. My chest tightened; my breath grew shallow. Whatever I chose to name them, the familiar physiology of self-reinvention had already begun. It was that freezing, mid–high-wire sensation Michael Bierut described in our recent conversation—except I hadn’t even stepped onto the wire yet. So I put down my phone and turned to the only consistent self-care practice I’ve ever managed, besides journaling: breathwork.

It began in the fall of 2020, when my quaranpod met daily for a thirty-five-minute guided breathwork meditation, followed by a cold plunge in a tributary of the Delaware River. I had never meditated before—at least not successfully. Traditional meditation, for me, had always been an efficient route to overwhelm: too much access to my own thoughts, unbridled, ricocheting around my brain with nothing to distract them. I had never located the calm that others promised was waiting on the other side. What I found instead was panic.

Truthfully, I had no real interest in breathwork either. What I wanted was to hang out with my friends. The first session confirmed my suspicions. Everything felt unfamiliar, suspiciously woo-woo. We followed the voice of a breathwork coach, Taylor Somerville, emanating from a phone speaker, as he led us through a gauntlet of instructions: breathe in and out through your nose; exhale through your mouth as if blowing through a straw; hold—keep holding—then inhale; from deep in your belly, fire breath. The body, it seemed, had suddenly become a syllabus—and I had not done the reading.

I didn’t enjoy it, exactly—though I also didn’t not enjoy it. It was sensory overload. My hands and feet tingled one minute; the next, I was being asked to visualize my breath—inhale green, exhale blue. But after the very chilly dip, I felt strangely buoyant—clear-headed in a way I hadn’t in a long time. So when our friend Liz suggested we do it again the next day, I surprised myself by saying yes.

What began as a one-off gathering became a daily one. Two weeks in, I noticed I was improving—not dramatically, but perceptibly. I could inhale more deeply. Hold my breath for over a minute, sometimes two. To my surprise, I was even enjoying the cold water. I felt calmer, more lucid. We kept going, meeting each afternoon and plunging into the nearby swimming hole until it froze over and winter made its position unmistakably clear. The group dispersed. I kept going on my own.

Breathwork steadied me. It gave me energy—something I badly needed at the time. I was persistently cloudy-headed and fatigued, a state I attributed to burnout and later learned was at least partly the result of a leukemia relapse.

It proved useful again when I had to pass a pulmonary function test in order to be cleared for my second bone marrow transplant. I was deeply anxious going in. I had faced the same test before my first transplant, a decade earlier, at twenty-three, and remembered sitting in a glass box with a plastic tube in my mouth, huffing and puffing only to fail again and again. The harder I tried, the less air I seemed able to draw, fear rising with each inadequate breath—because the consequences of failing were dire.

After a year of breathwork, I passed the test with ease on the first try. Not because I had trained for it, or even thought about it—but as a byproduct of returning, again and again, to a practice that helped me feel how I wanted to feel: energized, present, clear.

I may never cold-plunge again—I am, at heart, a scalding-hot-shower, luxuriating-in-a-bath sort of person—but I still practice guided breathwork several times a week. Sometimes for fifteen minutes. Sometimes for thirty. Sometimes for five, squeezed in between one thing and the next. It is the only practice I wasn’t instinctively drawn to that I’ve managed to make consistent. When I feel tired, uninspired, or overwhelmed, I breathe.

It can seem almost laughably simple. We breathe all day long. And yet I’ve come to think of breath as a kind of first draft—essential not only to staying alive, but to my creative life (and, frankly, my sanity). I’ve learned that when I’m overwhelmed or locked in battle with writer’s block, my breath tightens, becomes shallow, constricted. When I return my attention to it—when I allow it to move—the emotion and the thinking loosen, open. Feeling becomes information rather than force: something I can shape, revise, and return to.

I realize I’m beginning to sound like a breathwork evangelist. I promise I’m not being sponsored by oxygen. I’m sharing it here because it’s something I’ve come to lean on—a way to metabolize the overwhelm. We absorb enormous amounts of stimulus each day; some of it settles in memory, some in the body, and there isn’t always a mechanism for release. For me, breath becomes a way through it. Again and again, I notice it creates space—before writing, before painting, before opening a word doc and immediately deciding I need to reorganize my kitchen, before anything that asks for my sustained attention.

In that way, it mirrors something central to our New Year’s journaling project. This isn’t about achievement or accumulation. It’s about attunement—about how we feel on the other side of the page.

Today’s prompt lives right there, where breath meets form. It’s an essay from The Book of Alchemy called “Breathe Out,” by my friend, the poet and playwright Sarah Ruhl.

May it steady you.

Or open something.

Or simply sit with you awhile.

P.S. The coach I mentioned—Taylor Somerville—has since become a friend and very kindly recorded a guided breathwork session for us. It’s available to paid subscribers, if you’re curious (or just want to lie down and breathe for a while).

A few invitations—

Save the date! I’ll be in conversation with my very wise and very hilarious friend Kate Bowler this Tuesday, January 6, at 4:00pm ET on Substack Live. (We had a scheduling conflict and had to move it up an hour.) We’ll be talking about doubt and ambition—and how to build a meaningful life even when everything feels, technically speaking, like a bit of a disaster. If you can’t make it live, paid subscribers can watch the replay the following day.

If you’re just joining our 30-Day New Year’s Journaling Project, you can find the daily prompts here. And please come hang out with us in the chat thread. Benevolent lurking absolutely counts.

I also recently got to sit down with the actress, producer, and all-around mensch Jennifer Garner for a really beautiful conversation about journaling as prayer, noticing patterns, and how to make a shift when life feels hard. If you missed it, you can watch the full conversation here.

Prompt 363. Breathe Out by Sarah Ruhl

One summer, I was in Maine with my mother visiting a friend. We were on the front porch eating dinner, talking about a family friend, a beloved Congregational minister who had recently choked on a piece of steak at a restaurant. Though the Heimlich was administered and the steak came out, she died in the hospital two days later.

We moved on to other topics, and I brought out a pistachio cake. My mom took a bite and started coughing uncontrollably. I looked at her, alarmed, then ran into the house and brought her a glass of water. She took a sip, then started wheezing and spitting and grabbed a Kleenex from a pocket in her sweater. My mind raced; should I try the Heimlich maneuver, which I’d never done on an adult before? My mother was coughing and gasping all at the same time. Then, suddenly, she spat out a small blue object; it was a piece of yarn from her sweater, which had pilled and made its way into a Kleenex she’d used to blow her nose. She must have wheezed that little piece of yarn into her throat. We all relaxed, and my mom drank some water.

Relieved, I joked about how you worry all your life that some dreaded disease might kill you, not realizing you were going to be undone by your own sweater. The killer sweater, we all said, laughing. But after the relief of laughter, my mother started coughing again. She stood up, and the coughs turned into terrifying wheezes. She could not speak or catch her breath. My friend said, “She’s turning blue.” Sure enough, she was the shade of a blueberry. I screamed for a doctor, knowing full well that in rural Maine there would be none running over to save us. Time seemed to stop as my mother’s face turned purple and she gasped for air.

I hadn’t done a CPR course in thirteen years and I didn’t trust myself to do chest compressions. My mother was panicking. All I had at my disposal was my training in meditation, and I tried to find a little sea of calm under the rising tide of panic. “Mom,” I said, putting my hand on her back. “Try to focus on your out breath instead of your in breath. If you can just exhale, it will relax your breathing. Just one long breath out.” Miraculously, she heard me and started to exhale rather than gasping for an inhale that was hard to find. My mother’s wheezing calmed. The purple began to drain from her face. She was taking in oxygen. Her face turned pink again.

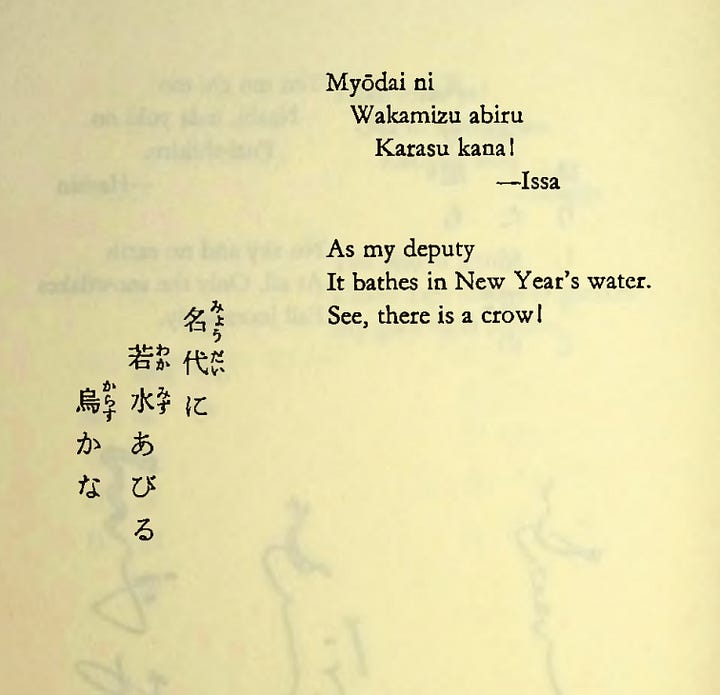

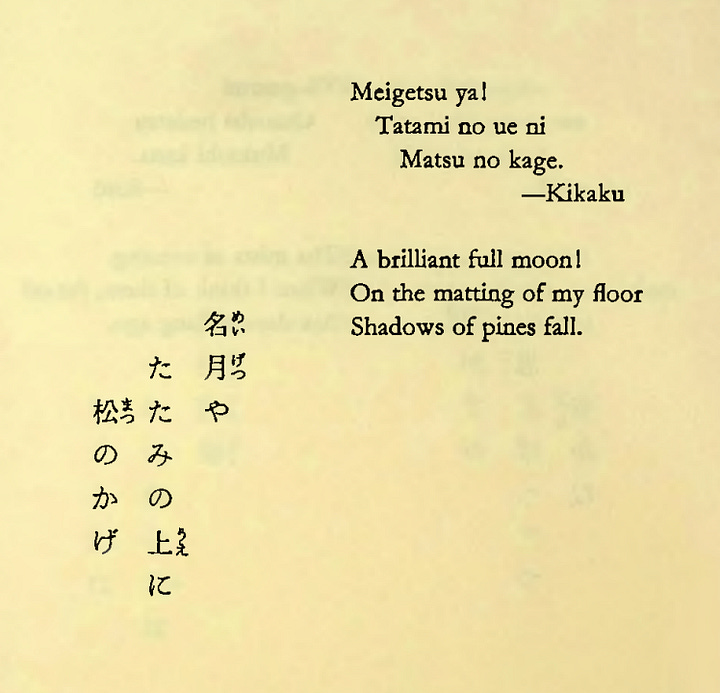

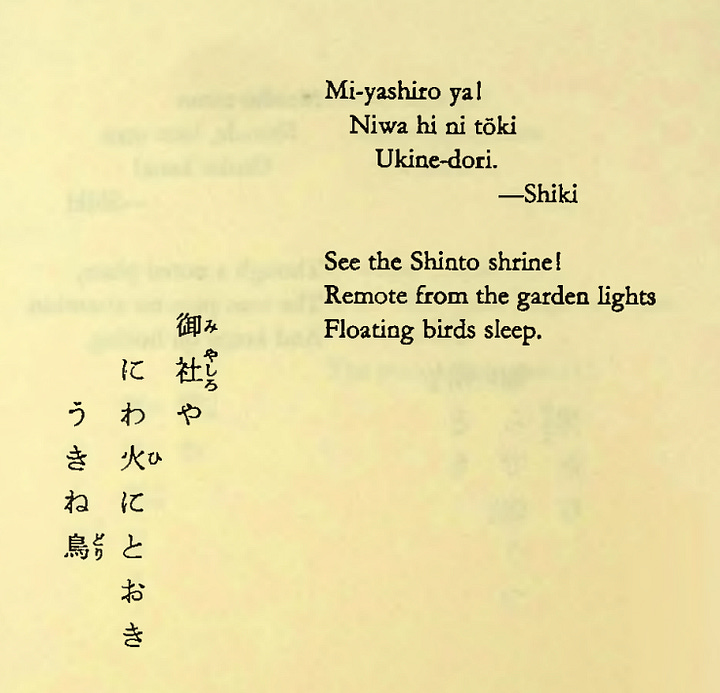

Over the years, I’ve picked up various meditation techniques. One is the simple 5-7-5 technique; you inhale counting to five, then exhale counting to seven, and then inhale for five again. Exhaling for two seconds longer than inhaling relaxes your nervous system. When I learned the technique, I thought, Wow, it’s like the haiku in breath form—5-7-5 syllables. I learned during the pandemic that haiku can be a form of journaling and a practice that can be done daily, with great benefit. I like to teach my students this 5-7-5 meditation technique and then have everyone write haiku immediately after.

This is your prompt:

Begin with a short meditation sequence: Close your eyes for a minute and count your breaths—on the inhale five, on the exhale seven. Repeat for as long as you’d like. Then look around you and write in haiku form about whatever is most present with you. It could be what happened to you that day, what’s going on outside the window, what is right in front of your face, or how your body feels in that moment.

For example:

A blue knit sweater that almost killed my mother—breathe out more than in.

Today’s Contributor—

Sarah Ruhl is a poet and playwright. Her plays include In the Next Room, or The Vibrator Play, which was a Pulitzer Prize finalist and Tony Award nominee, and The Clean House, also a Pulitzer Prize finalist and winner of the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize. She is the author of the memoir Smile, a poetry collection, Love Poems in Quarantine, and the co-author of Letters from Max, a deeply moving portrait of her friendship with the poet Max Ritvo, whom I met in treatment and, like Sarah, loved oceanically. A recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and the Steinberg Prize, she is currently on the faculty of the Yale School of Drama and lives in Brooklyn with her family.

Our 30-Day New Year’s Journaling Project

It’s not too late to join us. If you want, come spend January with us—one inspiration-sparking prompt a day, a little accountability, and a few chances to gather along the way. Nothing heroic required. Just a quieter, gentler way to journal your way into the year—together.

This prompt felt striking to my soul this morning. I so often find myself not breathing - like, fully NOT breathing - so often in my day. Perhaps a learned trauma response to freeze, and just like that, breath becomes stone. Focusing on my breath feels uncomfortable and effortful. So I find it a cosmic perfection that this prompt comes the day after I was nudged towards leaning into discomfort after the song from yesterday. Noted, universe.

My haiku:

Shame stills breath. But know:

I am … is a full sentence.

Come back to yourself.

What a joy to have this prompt today with a full hour to journal before a yoga class, and more breath work - yes, I am counting my blessings (!).

Breathing reminds me that how we fill ourselves can either sap and deflate or create life and breathing space. This year, I’m purposely choosing the latter.

Breathing, I let go

Releasing space for what’s next:

Possibility.