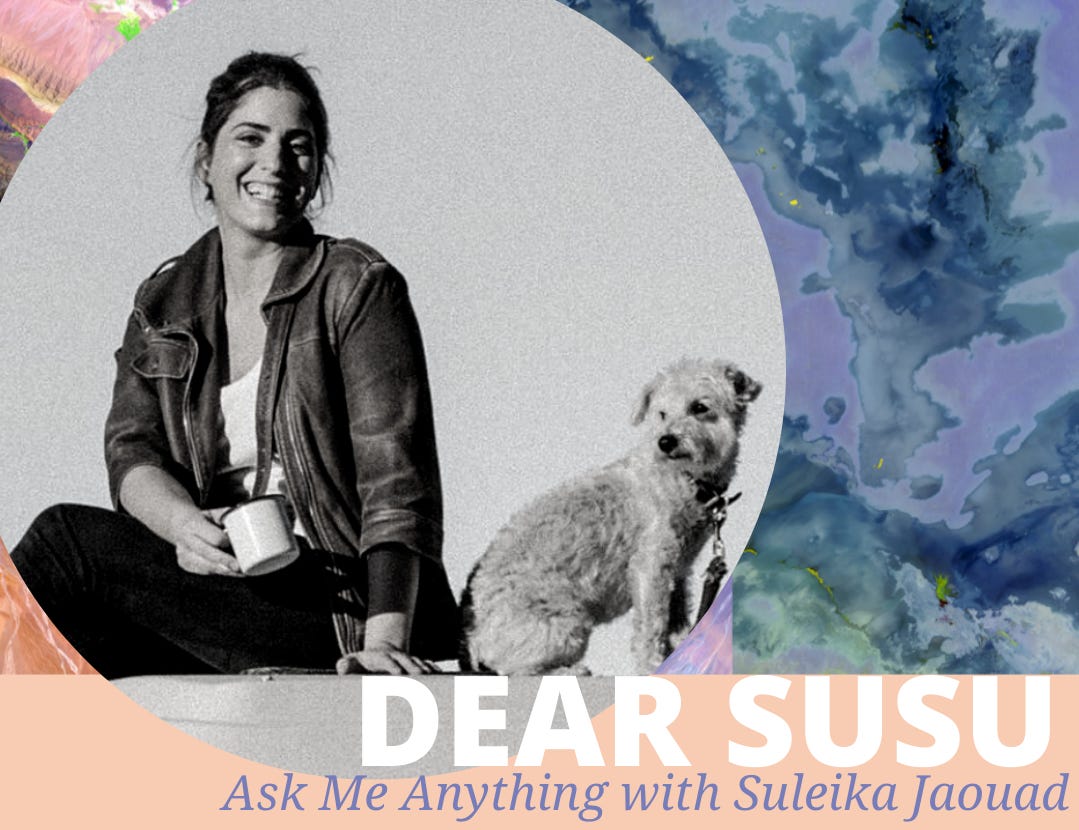

Welcome to installment #4 of Dear Susu, my advice column about writing and life and everything in between. Today’s question is from Terri, who in the face of a child’s life-threatening illness asks, “How do we keep going?”

For years now, I’ve been a student of how we share our stories and the power in that act. When I first started writing about my experience as a young adult with cancer in my New York Times column “Life, Interrupted,” I hoped it would be resonant with people dealing with illness—but what I didn’t expect is that people would interpret the theme of interruptions so broadly, and that they’d hear echoes of it in so many different areas of their lives. Even if their circumstances were wildly different, more often than not, they noted the similarities.

It’s such a beautiful thing, this yearning for connection—this desire to see, to be seen, to understand, to be understood. And I don’t think I’ve seen this in action anywhere as powerfully as I have in this community. It’s astonishing: a continual call and response, reverberations begetting more reverberations.

There’s strength in this collection of voices. In these connections, we build something: a larger story about the human experience, one that transcends the particular and becomes universal.

This was also true of the responses to Part 1 of “Love in the Time of Cancer.” My mom Anne Francey and I talked about the challenges of mothering a young adult with cancer—and the tension between wanting to protect and needing to let go. The comments section was soon full of the most moving stories—stories of mothers whose children were sick, whether it was cancer or epilepsy or Crohn’s disease. But it also resonated with a mother whose child is not sick but who’s struggling to allow her 15-year-old more independence, and a caregiver to three elderly parents, and a woman who is not a mother but is a nurturer by nature.

The conclusion reached by so many of you can be summed up by one: “It helps to share these stories—so we know we are not alone in our struggles.”

This is the powerful beauty of laid-bare storytelling, and also of this community. It’s such an honor to be part of this chorus with you.

Today we have the second part of “Love in the Time of Cancer,” where my mom and I discuss how we endure the suffering and the setbacks and how we anchor ourselves in humor and a creative practice. Again, I’d like to thank my mom for sharing her time and her hard won wisdom, and Carmen Radley, my dear pal and Isolation Journals collaborator, for editing this conversation so beautifully.

Without further ado, here’s Part 2.

Suleika: Mom, I want to read you a question that was particularly moving to me—and not only because I was initially struck by the many similarities. It’s from a community member named Terri.

Dear Susu,

I am sitting in the ICU at Memorial Sloan Kettering with my thirty-year-old daughter, Anjelica, who is going through her second bout of sepsis (first one was in the beginning of November). She has T-lymphoblastic lymphoma with a rare genetic mutation. She contracted Guillain-Barré syndrome over a month ago, rendering her unable to walk. Her goal is to be eligible for a stem cell transplant but an aggressive and stubborn cancer plagues her, plus she needs to be ambulatory.

We have been in the city since April 2021. I find that I have shut down a great deal. I remain steady for my girl, calm and comforting, but this journey is taking quite a toll on my being. I enjoy writing but I can’t seem to put pen to paper during all of this.

My query for you is this: How did your mother handle being a caregiver for you? How did she cope with your suffering, and all of your setbacks?

Suleika: “Steady for my girl, calm and comforting.” I so love that. The weight of the world in one paragraph, and beauty too. Mom, what comes to mind for you?

Anne: It’s a big question, right? How do we cope? Thank you, Terri, for sharing your story. From what I understand, you and Anjelica are not at home, and that might be the hardest part.

Suleika, the first time you were sick, we were commuting back and forth from the hospital to our home in Saratoga. That was hard in the ways we’ve already talked about—the unpredictability, the disorientation of so much travel, and how disconnected we felt as a family when we were apart. But at the same time, when we were home, I could go back to my little kingdom—my studio, or cooking in my own kitchen. Whatever force of habit allowed me to feel a semblance of normalcy. Your father is good at that. He has a lot of good routines. But it sounds like Terri moved to the city for her daughter’s treatment, and when you’re not in a place of your own, how do you sustain that?

I also relate to Terri’s struggle to put pen to paper, because I’m unable to do that as well. Words are too scary. Maybe it’s a little bit of what you’re going through, Suleika. You keep saying, “I don’t want to write. I want to make paintings.”

Suleika: Yeah, that’s true. I feel like I don’t have the mental energy to write, and for a while I was on a medication that blurred my vision, which made it impossible to read or to see what I was typing. I told someone that when I was trying to text, it was like writing with autocorrect on but in a different language—it was wild! But painting seemed like this thing I could do without any expectation of being any good at it. It was a medium where I could be imprecise and play and maybe even escape. And though I ended up painting these weird little portraits that nodded toward illness, it felt like I was approaching it on a subconscious or metaphorical level.

Mom, what about the part where Terri mentions shutting down? Have you ever felt yourself doing that?

Anne: Oh, yes. I totally relate to that, too. I remember the last time you were sick, I would walk back every day from the hospital thinking, “What is going to make me feel better?” You can’t go run in the park, because you’re too exhausted. You don’t want to reach out to friends, because that can also be exhausting; at times you find yourself reassuring them. Going to the movies—we did it once and it was the most frightening experience I ever had. [Laughs.] Because the sound was overwhelming, and I projected my own total disarray and fears, and they became magnified on this big screen.

How I handled it last time was by surprise. I observed that as I was walking from Mount Sinai Hospital along Madison Avenue, I felt like I was underwater, looking for a breath, and there was always a specific point where I felt like I was getting air back. All of a sudden, this balloon effect would happen—always at the same place.

So I asked myself, What is going on? And I noticed that it happened whenever I was passing a window with beautiful old sculptures of Buddhas and things like this. Maybe someone would say it was a mystical, godlike experience—and maybe it could have been, but that’s not quite my angle. To me, it was more about the beauty of the objects. It was art.

Suleika: Do you mean just experiencing art or making it? Or both?

Anne: Both. I kept making art, and then when we were in the city, I started going to museums like the Met or galleries whenever I could.

This time it’s been a little harder, because of covid. I asked your doctors, “Is it a good idea for me to go to the museum?” This was before you went in for your bone marrow transplant, and omicron was very bad, and they said, “Wait.” I was totally crushed. But I have found my ways. Like I go to galleries on weekday mornings, when there aren’t so many people.

In the past, there have been times where I’ve felt guilty about being in my studio making art, listening to the radio and hearing about all the difficulties in the world, and I’ve said to myself, “What luxury.” I have always believed art is essential—but at the same time, a luxury. And it turns out, it’s not. It’s a way to access the universal when our personal circumstances are too difficult. For me, it’s how I’m able to feel a little better. I need art to get through.”

Suleika: Another way you cope is with humor, right?

Anne: Yes, of course. That’s how I’ve coped since I was little. Again, this goes back to the thing about the mirror, and noticing what kind of energy the sick person wants. Because I have come with my jokes at times when it was totally unwelcome—when it was not reflecting the fear and anxiety you were feeling. Sometimes you needed me to be able to reflect rather than deflect that fear.

But laughing about things gives you a distance. It allows you to encapsulate whatever it is you’re struggling with, to express it in a roundabout way, to put the pain at arm’s length, to make you feel more joyful. So we have always done that in our family.

Suleika: Including Dad?!

Anne: Hédi, not as much. The other day, we were walking back from the hospital, and you had that terrible infection, and we were worried about all kinds of things like whether there was going to be some kind of organ damage. And as we were walking, he was so heavy, saying, “Oh, my goodness, it’s all so terrible.”

Again, these are our personal, individual ways of reacting. For him, he just expresses it and feels better, then he can move on. But to me, that feels unbearable—to hear him reflect on the hardest aspects of the situation and fixate on what might go wrong. I always say, “No, we don’t know. This is where we are now.”

We were walking a good thirty blocks, and at some point, I didn’t want to hear or think about it anymore. It was just too much. And what did I do? I discreetly put my headphones in, and I turned on beautiful classical violin music. And within a few minutes, I started feeling like I wanted to dance in the street. Not out of joy... but maybe.

It’s the same as humor, right? Joy can be found anywhere, and it’s important to keep looking for it. There was something so beautiful about being in the city, listening to this great music, being free to move, and saying no.

Suleika: [Laughs.] Did he know you were listening to music?

Anne: I don’t know. It was dark out. [Laughs.] But then I started singing with the music, so maybe he did. After a few blocks, he even started humming a little tune of his own.

Suleika: So often, when I read these questions from mothers with sick children, I think what a tricky balance it is. As a parent, you want to do everything in your power to take away your child’s pain, but there’s a limit to what you can do. And when you hit that point, you have to surrender. Do you think about the word surrender at all?

Anne: I just uttered that word to Hédi this morning. Because we have this uncertainty about where we are going to stay this summer. And will you need us in a few months or not? And are we useful? These kinds of things. We project so much into the future. You were even lecturing me about this the other day, when I was worrying about giving up my Fulbright in Tunisia when you relapsed. It was my first big break in a long time, and the thought of resigning midway through the year was such a disappointment and professional setback. But there was never any question that leaving to come be with you was the right choice—it was the right one. And as you keep reminding me, other good, unexpected things will happen. So you’re right—as parents, we have to surrender. If you’re too rigid, it’s too hard. It’s natural for us to try to control, but it’s less painful to surrender.

Suleika: Is that how you keep going in the face of those setbacks Terri mentioned? Or I guess maybe I should just ask it plainly—how do you keep going?

Anne: How do I keep going? [Pauses, thinking.] Someone asked me this the other day. You know I have a dear friend who is very sick. She has a terminal illness, and she is not offered any cure. Right now, her husband is totally overwhelmed, and he asked me, “How do we keep going?” I told him we have no choice. We just keep going—that’s how we keep going.

I’m always taking pictures, and I don’t really know why. The other day, I was at Central Park, and I realized I was taking all these pictures—probably ten different pictures—of the bridge tunnels. They were all so beautiful. You see silhouettes of the people passing through, all these different shades and shadows, and there’s light at the end. Only later did I make the connection. In these times when we don’t know how to keep going, it really helps to remember that there’s something on the other side.

To read about Anne’s art in her own words, see Cariatides de Papier: A Watercolor Diary.

Editor’s Note: We’re very sad to share the news that Terri’s beautiful daughter Anjelica died not long after she sent this letter. With Terri’s permission, we are still publishing Suleika and Anne’s answer in the hope that it will provide both practical and spiritual comfort to any other caregivers who are struggling to cope. In honor of Anjelica, we’re asking for donations to be made to the Lymphoma Research Foundation.

Have a question for Susu?

Just send an email to suleika@theisolationjournals.com with the subject line “Dear Susu.” Include your query, any necessary context, and a little info about yourself too. (If you wish to remain anonymous, that’s more than fine—just let me know or offer up a pseudonym.) I’ll answer as fully and thoughtfully as I can.

For more paid subscriber benefits, see—

Dear Susu #1: Read Me, See Me, Like Me, on sharing your words with the world

Our Studio Visit with Lena Dunham, on asking for what we need and the spiritual dividends of pain

On Hard Journeys and Packing Light, a community discussion inspired by Kate Bowler’s No Cure for Being Human

This this this: "It helps to share these stories—so we know we are not alone in our struggles.”

Such a relief to realize this! Thank you for giving us the chance to learn this lesson, Suleika and Anne. It's such a balm.

“How do you keep going?” This is something so many asked me when my 15-year old daughter was in cancer treatment. “She is so brave.” Another statement I heard over and over. Instead of comforting me, those statements angered me. In my own suffering mind, they made it sound as if we had a choice to be there, when the reality was that we had no other choice. And some days, I barely kept going and she wasn’t brave. I felt that by people saying that, we were obligated to be brave when sometimes I didn’t want to or simply couldn’t be. I wanted to be terrified, weak, vulnerable…because those feelings were real, not something I was forcing myself to be. I wish someone had said, “I’m amazed by your resilience,” instead because, while I was not always strong, I always kept fighting for my daughter…the love of my life. That was how I kept going. While it was messy and ugly sometimes, I did keep going for her because I love her more than anything else in the world and would give everything I have to support her in this terrible journey that cancer takes you on. I pray for you every day, Suleika. Your book has brought me much healing in my journey with my daughter. Thank you. 💛